The Art of Losing

1. Lazing in a field in Melbourne, I ask if he wants me to bring him back anything from Berlin, the city we’d shared. Straight-faced, he requests a photo of Bei Papa, the Currywurst kiosk that stood glowing till five a.m. by the stairs leading underground into our closest U-Bahn station. I laugh, tell him I’ll try.

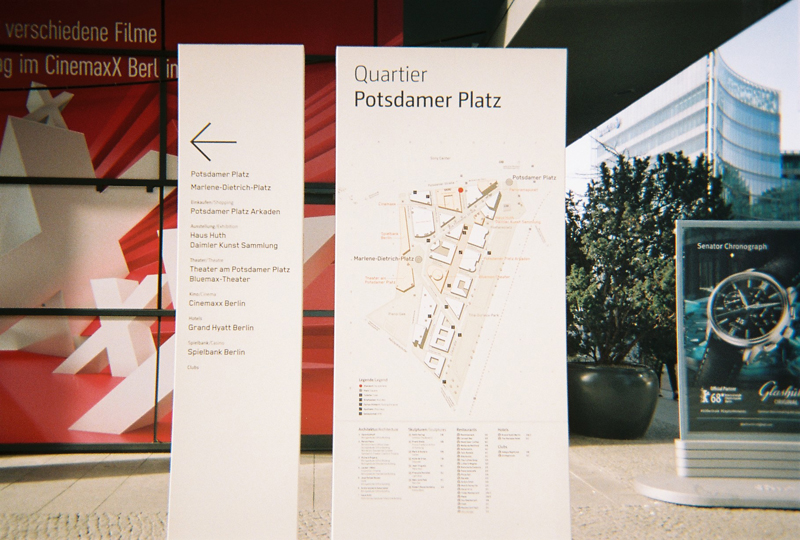

2. Potsdamer Platz in February is a terrible place for a festival. Paralyzing winds that people say come direct from Russia rip across the square. “Is there anywhere good around here to get a drink?” asks my producer friend, and those who’ve attended the Berlinale before laugh bitterly. The promised lands of Wings of Desire, Wim Wenders’s 1987 love letter to Berlin, have been mown clean and carpeted with concrete. Now there’s just money hotels law firms malls money. I shelter in the film bookstore Dussmann’s — shelves filled with canon coffee-table auteurs — and eye overpriced postcards for tourists. Am I a tourist now? I buy a few.

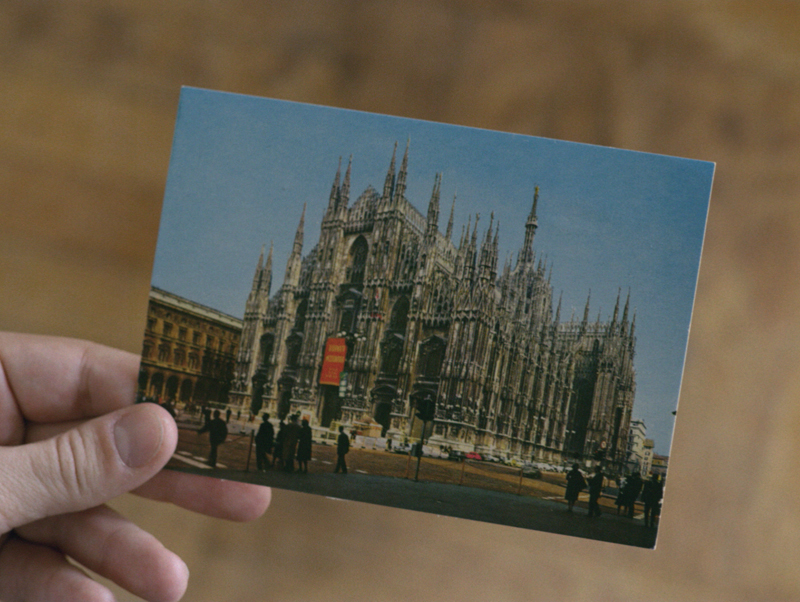

3. Writer/director/editor Ricky D’Ambrose is a year younger than me, and his debut feature Notes on an Appearance makes its world premiere on the fifth day of the Berlinale. There’s a postcard from Milan, a check from Dad, the clink of Brooklyn café porcelain, floaty millennials in clean shirts who never smile (wasn’t that one in the Piñeiro film?)… I can feel the critic next to me rolling his eyes. But then a third of the way through Notes, its protagonist David, an aspiring writer who moves to New York — and whose Bressonian innocence is dulled only by his banal halo of privilege — vanishes. He leaves nothing but a paper trail in his wake.

Within the stuporous festival space of on average three films a day, D’Ambrose’s film leaves me reeling. I watch it again.

4. Notes is sixty minutes. Exacting. Every piece counts.

Frederic Schlegel: A fragment, like a miniature work of art, has to be entirely isolated from the surrounding world and complete in itself like a porcupine.

Anne Carson (Sappho):

]

]

]

]

]

] in a thin voice ]

5. Originally a sprawling drama entitled The Millennials, D’Ambrose’s manuscript was culled to “a scrapbook movie” (his words). The action is breezily conveyed, miniaturized, through documents left behind: notebooks, diary entries, New York road maps, faux-articles from newspapers and hip literary publications, lists of expenses. The editing is acidic.

6. In the same festival, Steven Soderbergh premieres a film whose entire camera department fit inside his backpack.

7. When old Berlin friends ask how I’ve been, I am cool, careful with my words. I talk instead about the films I’ve seen. Recount the exhilarating palette: the buttercup yellow of David’s shirt; the warm brownstone of Brooklyn streets.

8. Notes is simultaneously snappy and idle, flippant and somber — a neat mirror of a generation. In my remake, every character is played by Lana Del Rey, wearing her diamond halo from the Grammys, angelic and aloof.

9. Taking a night off, a group of us younger critics run to catch the bus to SO36 where there’s a rare festival party that isn’t awful. “This is where Bowie used to hang,” someone coos. We dance to a post-punk band whose members wear scout uniforms and I recognize the synth player, a leggy Frenchman who, years ago, came and ate stew at my apartment. In less time than it takes to order a beer from the crowded bar, a British critic friend and I lose a game of Kicker to two older, surly locals. They dismiss us from the table like the sightseers we are.

10. Because I was too cheap to buy a disposable camera with a flash, most of the photos I took for this piece came out unusable.

11. David stands at a window with his back to us wearing that shirt I love, and says, “From the fifth floor you could see the rest of the neighborhood. There’s a big construction site across the street. For a new apartment building, I think. Todd told me that the whole area would be unrecognizable in a year. I tried to imagine the new view.”

12. The sun emerges so oh why not I make the journey. It seems that in the years between when I left and then returned to visit Berlin, the entrance to Tempelhof — the Nazi-built airport-cum-public park — has been extended, beautified. If I were to enter and cross the park, I’d reach Platz der Luftbrücke where, in the passageway of the then-West Berlin station, Isabelle Adjani undergoes a (literally) monstrous miscarriage in Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession (1981). She smashes milk and eggs across the tiled walls, her body leaks blood and pus-like fluids across the floor. The film was written during the Polish director’s own traumatic divorce. Instead, I linger in the spot on Hermannstraße where I think our red and yellow-striped kiosk stood; the pavement feels much too wide.

Elizabeth Bishop: I lost two cities, lovely ones.

How vain it is to mourn the passing of a kiosk in a city built on swampland, steeped in loss.

13. Normally in movies it’s the women who go missing: Lea Massari in Antonioni’s L’avventura (1961), Otto Preminger’s schoolgirl Bunny Lake (1965) or those lacy colonial fantasies populating Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975). To go missing is different than losing oneself. Rather than a wilful departure — almost always the territory of road movies, men — the genre is shorthand for tragic violence done.

14. “I miss you” is a phrase hackneyed enough to slip into the body of an email without the recipient really noticing.

15. Where did they go? David, yes, but also: smartphones, the internet, the screens and virtual spaces in which we spend our waking days. No character holds them, much less speaks of them. Though the film occupies a concrete historical moment — stickers and posters give us Black Lives Matter, Refugees Are Welcome Here, I ❤ Brooklyn — this technology has been erased. “You can’t just pretend it doesn’t exist!” says my eye-rolling friend. “Why not?” I ask. Working as an archivist, David watches a series of VHS holiday tapes (waves crashing on a beach; the World Trade Center towers seen from a ferry) and records their contents on paper. Brooklyn passes like an uneasy daydream, a decoy memory that could give way at any moment.

Stephen Taubes: Violence, the great antidote to historical thinking.

16.

17. The documents pile up but lead nowhere, mean nothing. What does it mean when, in this late stage of capitalism, we can’t read an image, can’t foresee an alternative, can’t orient ourselves in a distinct here and now, or make out what dangers lurk around a corner? How do you chronicle loss? In Jean-Luc Godard’s Detective (1985), the truth is said to be “between appearing and disappearing.” Any answer, he warns, is smack bang in front of us and forever out of sight.

Note: Images four and nine are taken from Ricky D’Ambrose’s Notes on an Appearance (2018). Courtesy Graham Swon and Ricky D’Ambrose.