Eternal Ephemera

In May, a few weeks after finishing my undergraduate degree, I packed my life into a suitcase and moved from West Philadelphia to the West Coast. Perhaps it’s because this physical move mirrors the metaphorical jump into the unpunctuated abyss of “the rest of my life,” that I feel an intense sense of excitement matched only by a sense of panic. This not-so-gentle shift into adulthood is utterly freeing, and allows for a certain liberation from my past selves; but of course freedom is daunting, and often results in self-reflexive questioning, a recursive loop of hyper-awareness and self-doubt. As Icelandic artist Katrín Sigurdardóttir succinctly put it, “I guess the older I get, the less secure I am of any knowledge that I have.”

As I was packing my things, I discovered a printout I’d made of a reading which my favorite printmaking teacher had assigned earlier that year. Telling Objects: A Narrative Perspective on Collecting by Mieke Bal, a Dutch cultural theorist, argues that we can learn a lot about our subconscious selves by examining our belongings. The act of collecting is a “human feature that originates in the need to tell stories, but for which there are neither words nor other conventional narrative models.” Collections allow for a retrospective understanding of self, revealing an accumulative “eagerness that can only be realized after it has developed far enough to become noticeable.” As I scanned my room, I thought about all that I had amassed over the past twenty-two years. My most noticeable collection was the scattered piles of paper covering every surface: Birthday cards sent from my grandmother, a business card for my algebra teacher’s failed homemade hummus company, a flyer advertising my university’s all-female sketch comedy show, a list titled “May 2016 Goals (Unfulfilled),” a ticket to the Texas State Fair, pencil-drawn comics detailing awkward pre-teen encounters.

I’ve always felt attached to these tactile and tangible markers of time. I can’t quite define the joy I gain from encountering these materials — collateral goods whose lifespans were not meant to last this long. They remind me of moments, people, or events I would have otherwise forgotten. They jog a memory, nudge at my side, and say, “Hey, remember who you were back then?” I compulsively collect these objects, holding on to younger selves which, at one time or another, I felt so eager to shed.

•

The archives at SFMOMA include exhibition invitations, posters, catalogues, dialogues between in-house designers and printers, and much more. Most of these items are housed in the Collection Center, a 75,000 sq. ft. warehouse in a dusty, industrial stretch of the city, containing the bulk of the museum’s holdings that aren’t on display. Thinking about my own collection of ephemera, I saw these print materials as a personalized gateway to the museum. They point to histories, memories, and events; sprinkled with crumples, folds, stains, and tears, they reveal a human touch and intervention.

How do these seemingly secondary and often overlooked objects speak to the museum’s permanent collection? How does one inform the other? Most of the archived prints are not necessarily “artists’” ephemera; they were not created by an artist or for a particular project. They often pre-date their “Art” counterparts. Do they speak to a more immediate zeitgeist because of the nature of their creation and distribution? They continue to look toward a future that is now passed.

•

•

•

•

•

Snøhetta, Oculus Bridge, 2016

•

•

In their initial distribution, most of these materials were largely promotional, created and distributed to gather attendees for an exhibit, invite members to a panel discussion, promote an upcoming party. What happens when the party is over, the exhibit long gone?

Art asserts its permanence, declaring that it deserves to be kept, bought, sold, collected, and displayed. We ask how art functions in a broader historical, political, or societal context. We celebrate works that operate on a visceral level, eliciting some deeper emotional response or sensation, transcending time and place. Yet the indefinable exhilaration I felt when encountering my collection of paper goods isn’t unlike the subliminal emotion I feel from staring at Agnes Martin’s subtle paintings.

Something happens in the accruement of explicitly dated materials: Their use-value shifts. In the decision to save, collect, and revisit these tangible pieces of ephemera, we convey on them an array of emotional undertones, such that they no longer feel like mere marketing materials. What if you decided to keep the above 1996 Holiday Party invitation because you met a special person there? Or the Printographic Art panel discussion invitation reminded you of a meaningful conversation? While the museum’s collection isn’t a personal collection, I still felt a sentimental joy when sifting through its archival boxes. As Bal suggests, collections help develop a sense of self, both for collector and spectator. The ephemera files let us peer into the institution’s subconscious, reminding us that somewhere along the way, human beings made the decision to keep these things.

•

Packing up my life meant getting rid of many collections. One of the first to go was my pile of papers: receipts and to-do-lists accumulated over the years. At first, this was hard. I wanted to save these records, ripe for nostalgic review. But after tossing piles of old notes and magazine tear-outs into the recycling bin, a surprising calm washed over me. Like my paradoxical sense of freedom, I felt an independence in leaving these items behind: maybe it’s precisely because they’re so poignant that they were necessary to relinquish. Maybe it was just the right time to untether myself.

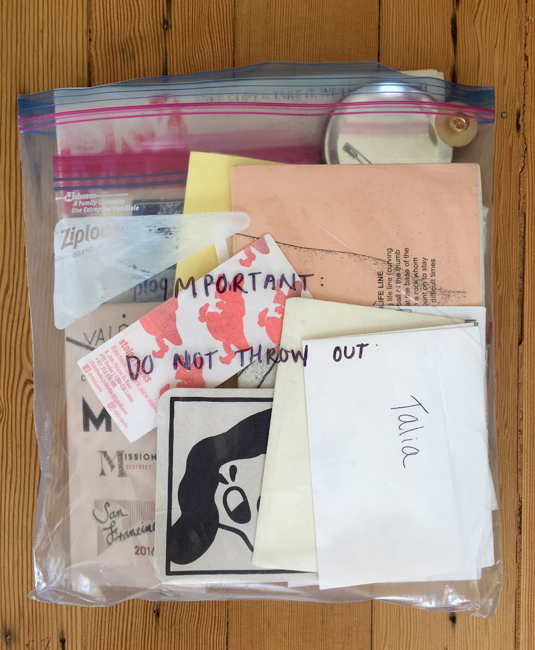

Still, I did save one zip-locked bag. Stuffed with papers, it’s labeled “Important. Do Not Throw Out.”