Dark Times

I

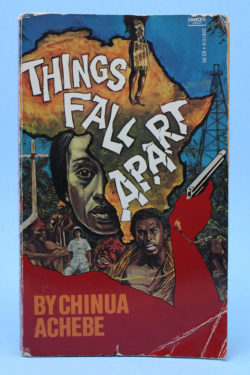

Saidiya Hartman asks: What are the stories one tells in dark times? [1] She answers by borrowing from Michel de Certeau, who recommends “recruiting the past for the sake of the living.” [2] Both statements bring to mind Chinua Achebe’s 1958 novel, Things Fall Apart, and its role in shaping the imaginary of the African Revolution. By the late 1950s when a young Achebe started working on the novel, Africans were agitating for a new dawn in politics, breaking from European colonization.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer,

Things Fall Apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world

— W. B. Yeats

The persona of The Second Coming describes a kind of apocalyptic imaginary. The images in the second stanza are otherworldly, dreamlike, echoing the coming of a beast similar to that in the Book of Revelations. Yeats’s words preface a prophetic novel that describes a rapture in 1890s Nigeria and prophesies coming raptures in twentieth century Africa.

II

A gyre is a kind of vortex. For Yeats, it is a state of vertigo: a sensation of the mind. It could be the result of intoxication, or of whirling in circles on a fixed axis, causing the medulla oblongata region of the brain to lose its center. This state of things is implied in the poem: “Things Fall Apart” because “the center cannot hold.”

//

The apocalypse is in the sense of its lead character, Okonkwo, sinking into a vortex of sorts. It is a state of mind. A mental apocalypse occurs: not as Yeats’ lyrics embody the incredible moral decline of World War I, but rather through an apocalyptic village drama. An Igbo man, Okonkwo, whose ambition in life is not to become his father, Unoka, falls from greatness, then dies a sudden death.

III

The turning and turning points to the dizziness of time — that of Louis MacNeice’s déjà vu [3]; it not only describes Okonkwo’s sudden fall from greatness, but also shows that the village is a state of mind in which “[i]t does not come round in hundreds of thousands of years, it comes round in the split of a wink.” This thing coming round in the split of a wink is the generational rupture in village time.

Time goes by so fast that it leaves him dizzy from the vertigo of it all. The quickness of time shows the unexpected.

IV

We have done our duty

by our people;

We met the challenge of history

and were not afraid

— Kofi Awoonor

Addressing the crisis of time, Kofi Awoonor speaks of planting corn, harvesting, filling the barns, and feeding his people. We see the details of not just one man’s account of his life, we see the lives of many. The challenge of history is met with a commitment to the continuity of the people as a whole. Village time is occurring within the continuity of his people, the feeding of his people, the harvesting of corn, and the planting of it. How this becomes a duty and a challenge to history is, also, the philosophical framework of Things Fall Apart.

V

For all this happened before and we have all been through the mill. [4]

— Louis MacNeice

Early in the novel Things Fall Apart, Unoka visits a friend in order to ask for help. “I have come to you for help […] perhaps you can already guess what it is. I have cleared a farm but have no yams to show. I know what it is to ask a man to trust another with his yams, especially these days when young men are afraid of hard work.” Unoka admits too easily what we all have been through; that is, the mill. The difficulty of meeting others’ needs and facing the challenge of history.

//

VI

Historically, Achebe points to how societies in Nigeria have survived through agriculture. In Igbo culture, the harvest is not only a sign of survival, but it is a sign of continuity of time: that is, because we have had a good harvest, a good year is to follow. In this sense, a poor or bad harvest signals a bad year to come, or even that not only human failures are present, but moral failures too. Time is disrupted in this sense. Apocalypse refers, then, to this discontinuity of good harvests, plentiful and fresh yams, and the coming of the shrunken yams.

VII

Father and son, Unoka and Okonkwo, are depicted as two different kinds of men. Okonkwo is the “strongest man in Umuofia” and Unoka’s sacrifices are worthless if he doesn’t farm his land. Okonkwo became a model for African nationalism — the politics that began first amongst African students in St. Petersburg, Russia. Okonkwo, a fictional character, seemed to fill the rather empty shoes of an emerging African nationalist of the 1950s — his ruthlessness became the mode du jour for the anti-colonial struggle. Things Fall Apart represents the past, while the self-sacrifices of Okonkwo show the rapture of village time. Yet the novel predicts a future of further raptures in Nigeria’s politics, identity, and ultimately, its people.

VIII

Beyond Nigeria, and beyond Africa, a number of ruthless Okonkwos have recently emerged. Forgetful of their obligation to history and to people. Things Fall Apart is a reminder of what happens when time is no longer shaped by the well-being of land or earth, but rather through the swaggering pride of people in power. When we see an Okonkwo at the helm of world politics, there are dark times ahead.

Notes:

1 Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in two acts.” small axe 12.2 (2008): 1-14.

2 De Certeau, Michel, and Tom Conley. The writing of history. Columbia University Press, 1988.

3 MacNeice, Louis. “déjà vu.” The burning perch. London: Faber and Faber, 1963.

4 MacNeice, Louis. “deja vu.” The burning perch. London: Faber and Faber, 1963.