Notebooks on Notebooks

No subject can easily be conceived as extinguished. Language doesn’t allow that thought; its trajectory is always to lean forward into life, to push it along, to propel the dead onward among the living.

—Denise Riley, Time Lived, Without its Flow

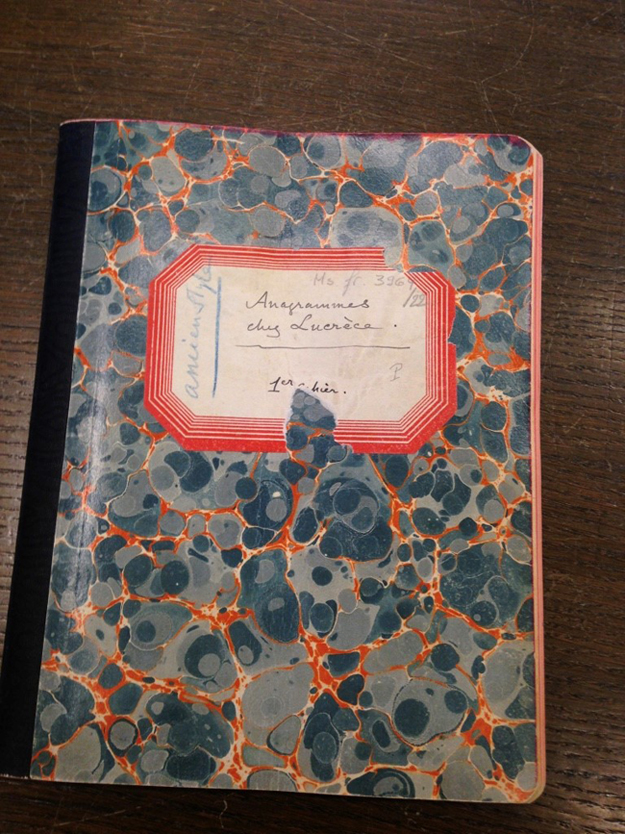

In 1906 Ferdinand de Saussure begins the anagram notebooks, late and in mourning. In a work of deferral to stay his own dislocation, he pauses from the job of transmission at the Université de Genève. His lectures, composed for speech alone, delivered in his slow aristocratic intonations, are held in abeyance. After the death of his father, Henri, he departs for Rome, a silent hiatus. He walks in suspension among the ruins, crumbling stones monumentalizing the dead. Their inscriptions summon a passerby to reanimate a voice. “The reader is a vocal instrument used by the written word…in order to give the text a body, a sonorous reality.” 1 The letters perch, holding the marked remains, dependent and alluring. Then with the passerby’s attention caught, the stone aches to breathe through the living, while the living lends sound to the inscription. For an instant, united in breathing, the voiced letters resound: “Stop traveler, I, a great poet of ardor, was killed by my learned love.” The traveler self-addressed is complicit, pronounced accomplice to the dead. Reading aloud the Saturnian inscriptions on ancient tombs, Saussure hears sound patterns: vowels echoing vowels, words within words. One hundred years later, I am that traveler whose attention is caught.

Praeterea partis in cunctas dividitur vox,

ex aliis aliae quoniam gignuntur, ubi una

dissuluit semel in multas exorta, quasi ignis

saepe solet scintilla suos se spargere in ignis.

ergo replentur loca vocibus abdita retro,

omnia quae circum fervent sonituque cientur.

—Lucretius

[Meanwhile, the voice is dispersed in all different directions,

since one voice engenders another one, once born,

voice springs apart into many voices, just as a spark

of a flame often sprinkles itself into many flames, so places,

out of the way and hidden, are indirectly filled with voices,

swarming all around and boiling with sound.]

I’m walking with Bob Glück in Scotland. It is raining on and off, and we are meanwhile together, in a near-mythic garden: Little Sparta, the lifetime work of Ian Hamilton Finlay and his many collaborators. In the roaming gardens, time grows and reforms in cooperative cycles, a concert of creating between the living and dead, chance and weather. It survives its makers. Yet I’m reluctant to consider Little Sparta a monument, remembered by its stones and wooden posts; it’s too inclusive and capacious in its attention, its various passions compelled in plant life and in plays of language, the syntax overgrown with new intention, relations and histories entwined. What’s been forgotten or abandoned — unattached relics release flowers and time. We encounter initials and imperatives, commands inscribed to no one in particular: visiting birds, sheep, deer within the dwelling, whether migrating or permanent residents. Each area with its containing name (Julie’s Garden, Wild Garden, English Parkland) evokes bodily relation, gestures surprised in their tracks. The day is covered in gray. Our approach to Little Sparta is on foot via a dirt road, Stonypath, through meadows of grazing sheep and their lambs; these pastoral enclosures suggest a different economy from that of accumulation, a time when weather reigned. The caretaker invites us to enter along the many footpaths. Bob and I understand tacitly our desires to wander alone, to allow for our own curiosity, moved along by different tempos — mine glacially slow, Bob’s his own.

SEMPER FESTINA LENTE

[always make haste slowly]

No birdsong midday. Its absence focuses me for the parsing of Latin and Greek texts sprung on and among monuments, stones, posts, trees. Lines from Virgil’s Georgics, wind on the turf around the trunk of an elm tree. The encircled letters insist on circular reading while pacing in dactylic hexameter around the tree.

ILLE ETIAM SERAS IN VERSAM DISTULIT ULMOS / EDURAMQUE PRIUM ET SPINOS IAM PRUNA FERENTIS / IAMQUE MINISTRANTEM PLATANUM POTANTIBUS UMBRAS

[That man even transplanted slow-growing elm trees in rows and blackthorns and pear trees, already bearing fruit, and a plane tree furnishing ready shade to those who take shelter to drink.]

These are from his fourth georgic, the one that gives advice on beekeeping. After several hundred lines of didactic verse on the stewardship of bees and their social mores, Virgil turns to illness and the story of Aristaeus. His bees are dying. To heal them he searches for aid and answers along a perilous trail. At last he subdues Proteus in his watery cave, who reveals the reason for his ailing bees. Unwittingly Aristaeus was the cause of Eurydice’s death, and widowed Orpheus has to take his revenge. Then in one and the same rite, simultaneously the singer is appeased, and the beekeeper learns the secrets of bee auto-generation.

Virgil renders the aching final moments between Orpheus and Eurydice. Leading her from the infernal realms, he falters at the rim; almost safe, save for his need to see her, to be sure she is there. Rather than mending, he ends it again. Both the beekeeper and the twice bereft singer share in her doubled death.

Meanwhile, these lines circling the elm form part of a praeteritio; that is, the story I am not going to tell but in mentioning what I won’t tell, end up telling it all (also known as the gossip’s ploy). The verses speak of a gardener, an old man from Corycus, who, like Finlay, has made much from a plot of unpromising land. My reading steps enact the relations between eras and elms, between these discrete yet congruous gardeners, in an aside that can’t be left unmentioned.

The gate to this enclosure left open reads: ECLOGUE. I follow the line of fold until I am halted by this:

This post, whether marking passage or embrace, is part of a magical stile (style?). It’s not the typical a-framed ladder which hardly alters one’s gait, while leaving the four-leggeds inside or out. But this stile of radiating steps proposes a circular view of our surroundings. Winding around like a helix with the fence as the axis, the quiet, immobile center, it demands of me a choreography: lifted leg, twist, another lifted leg, spun round. Fence/gate thesis/antithesis.

And I land, unfurled and dizzy, to read the pole’s opposite side: “SYNTHESIS stile”

‘Their foes and mine are lawless foes

And L—ws thems—s they hold

Which clipt-wing’d Justice cant oppose

But forced and yields to G—d

There are f—s of mine and me

These all our Ru—n plan’d

Altho they never felld a tree

Or took a tool in hand

—John Clare “The Lamentations of Round-Oak Waters”

At last and finally the alphabet’s letters are unburdened of their task to render what they imperfectly mark, a relief underscored by wild soundings of flowers and their friends. Meanwhile the letters still scratch on whatever surface with whatever’s at hand.

NO RIPE RASP

(Proserpina :: Persephone :: she, who traffics annually between the infernal and earthly realms, having been abducted by Pluto while picking flowers with nymphs. Her mother, Demeter, steadfastly searching, while divinities make deals. The fall out — pomegranate seeds, a split subject, here in Finlay’s garden graffitied letters divide into anagrammatic figures; Proserpina’s name in parts.)

Dickinson, Emily, 1830-1886. Poems: Packet XXXIV, Fascicle 21. Includes 17 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Houghton Library – (186a) Our journey had advanced, J615, Fr453.

Bob leads me to the horizon, expanses near endless and wayward, while I diagram sentences. In Lund, in Sweden, inside the Romanesque cathedral, Bob is eager to stand me in front of a tower of timekeeping. Two kinds of clocks.

The upper is the Horologium mirabile Lundense, dating from 14th century, an astronomical clock whose dazzle of golden dials and signs regularly asserts astronomical information — the slant of the sun in relations to the positions of the moon relative to the constellations. Layered between the two clocks is a row of doors, from which, at the noon hour, appear the three magi who circle around the virgin and child and then retreat for a respite to their dwellings between. An internal organ plays in dulci jubilo to accompany the magi and their retinue.

Bob remarks that we are hearing music as it was heard and has been heard for over 600 years, not only the music but its tempo, the pace of a moving march, the real thing, a tempo impossible to reconstruct from surviving musical scores that lack fixed time signatures. But here we hear this ancient beat, stepping through several hundred years to the present. I love how much this thrills him, his allegiance with the music’s tempo, their solidarity.

The lower clock is a calendar clock, working within a more linear though cyclical set of references. How could I accommodate much less convey the scale of these timepieces, their perspectives, their possible relations? With capacious gestures the lower one keeps track of the year, month, day. It can tell you what day of the week a certain holiday will fall on in any given year. And in a yet larger scale, the outmost circle moves through golden astrological rotations, framing the whole of durations. To the side perfectly at the meridian sits Father Time, cloaked in white with white beard, eyes unfocused. He holds a long pointer that extends towards the middle and, like him, is aligned with the meridian of the circles. Another horizon. May 24, 2016: on the cusp between Taurus and Pisces was when we were there.

Then Bob takes me to eat kardemummabullar; having tried many, he’s decided the ones from St. Jakobs represent the best of their kind.

These clocks can account for the movement of the sun and planets, the constellations’ trajectories through the sky, and holidays projected into the future. They do not, however, tell time.

The sundials we encountered along the paths of Little Sparta, which on account of the gray day, only faintly suggested our moment. One sundial, surrounded by strawberries, speaks in its first person.

The ten syllable iambic phrase seems to imply that the utterance itself not only describes the marking of time but makes time itself, a moment hidden that needs only light to reveal itself in its own pronouncement of what can never be uttered accurately or timely enough.

But what happens at night? Time sleeps: Hypnos, the brother of death.

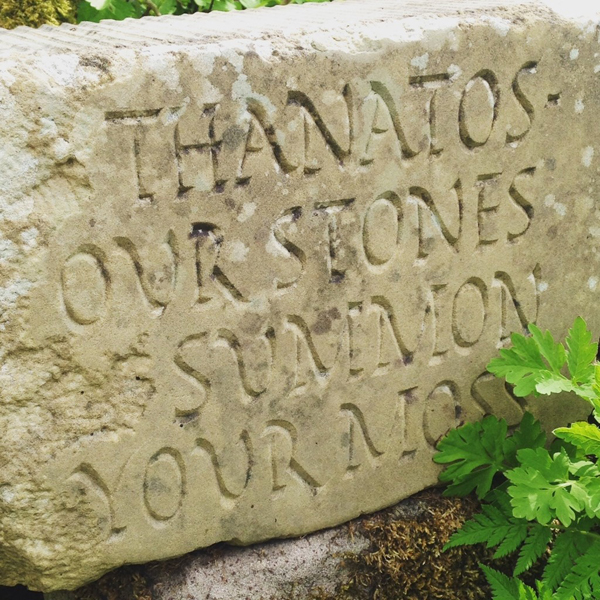

This conversation between moss and stone, their invocation of death, rehearses a motif I’ve been following along with Saussure — how do the stones speak and how do we lend our voice to these stones, these who in fact speak for themselves. As if grief would unite us via this enchanted supplement to mourning, the moss is called on to clothe its stone body with a vital garment borrowed from death.

AVE WAVE UNDA VALE

Farewell Wave Upon Wave Adieu

Multas per gentes et multa per aequora vectus

advenio has miseras, frater, ad inferias

ut te postremo donarem munere mortis

et mutam nequiquam alloquerer cinerem.

Quandoquidem fortuna mihi tete abstulit ipsum.

Heu miser indigne frater adempte mihi,

nunc tamen interea haec, prisco quae more parentum

tradita sunt tristi munere ad inferias,

accipe fraterno multum manantia fletu,

Atque in perpetuom, frater, ave atque vale.

—Catullus 101

[Through many nations and across the great sea, carried along

I arrive, brother, for these miserable funeral rites,

so that I might give to you death’s final gift

and speak in vain to silent ashes.

Since Fortune has taken you yourself away from me,

Ah, sad brother snatched from me cruelly

now nonetheless, meanwhile these things, ancient and ancestral,

are handed over, the sad work of burial rites,

receive them, drenched thoroughly with brotherly tears,

and always forever, brother, adieu and farewell.] 2