Keep Your Heart Strong: An Interview with Kati Teague about Healing from the Prison Industrial Complex through Art and Organizing

In this mini series I interview three young artists and recent graduates of UC Santa Cruz whose work addresses policing, state violence, and creative forms of resistance to the prison industrial complex. The second of these interviews is with Kati Teague, whose series Have You Seen My Mother? reckons with her experience of her mother’s incarceration. It was created for the 2013 Irwin Award Show, a group exhibition recognizing twelve emerging artists and graduating seniors at UC Santa Cruz’s Sesnon Gallery. This series is cross-posted on Organizing Upgrade.

For the past several years I’ve worked in the prisoner rights and anti-prison movement with the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP), an organization that supports women and transgender people locked up in California’s state prisons and county jails. The education I’ve gained about the impacts of the prison industrial complex on women and mothers is immeasurable. The stories told to me by prison survivors and those currently living behind prison walls make clear the gendered and racialized violence endemic to a system that falsely purports safety and protection as its function — stories of the court’s refusal to include evidence of self-defense in trials involving intimate partner violence, the inhumane and negligent regard of those pregnant or giving birth in custody, and the long and painful process many mothers face in reuniting with their children after they’ve been released from prison.

In January 2013, CCWP was part of a coalition that organized a statewide mobilization to Chowchilla to protest the inhumane conditions at Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF), currently the most overcrowded prison in the state. The rally, initiated by and organized with CCWP’s incarcerated members, brought into sharp focus the gender discrimination explicit within California’s ongoing prison crisis; over 400 people from throughout California traveled to the Central Valley to amplify the voices of those inside and bear witness to these abuses.

Two weeks after the rally, while teaching an art course for graduating seniors at UC Santa Cruz, I met Kati Teague. Kati was among the hundreds of people who attended the rally; her lessons about the prison system came years earlier, during her adolescence. Kati’s mother was incarcerated for two years in CCWF, an experience she suppressed until eleven years later, when she traveled to the Central Valley to stand for the first time in front of the prison where her mother was held.

This experience profoundly changed Kati. Surrounded by people whose families shared the burden of a similar absence, Kati began to understand the collective impact of this systemic removal of mothers, grandmothers, siblings, and children from our communities. While it had been over a decade since her direct contact with the prison system, the gathering crowd of protestors made clear that the crisis of California’s prison system was far from over. However, in order to fully reckon with the experience of loosing her mother to prison, Kati did what artists do: she made art about it.

During our studio visits, Kati’s hunger for information and action was palpable. She was eager to learn all that she could about the history of California’s prison system, how people survive the brutality of imprisonment, and the ways people are fighting back on both sides of the walls. And the education was reciprocal; talking with Kati helped me further understand the prison system’s insidious and relentless mechanisms of punishment that function to traumatize not only those who are locked up but their family members, too. With every story of a parent separated from their family is the story of a child left to make sense of this rupture.

In this interview, Kati discusses how she uses art to repair her relationship with her mother, the necessity of unlearning the oppression that allows prisons to exist in the first place, and how her art practice and new-found passion for organizing heal backward — as she comes to terms with the ways in which her mother’s sudden and forced removal from her life deeply shaped her — and forward, as she commits to working against the prison industrial complex and toward justice for all those impacted by this invisible punishing machine.

Project WHAT! Youth With Incarcerated Parents marches at the Chowchilla Freedom Rally, January 26, 2013

Adrienne Skye Roberts: Let’s start with your experience at the Chowchilla Freedom Rally. Can you talk a bit about how that kick-started your recent artwork?

Kati Teague: This whole art project started because I went to the Chowchilla Freedom Rally — that was the entire impetus to do this work. The rally took place at the prison where my mother was held. I was never allowed to go there because she didn’t want me to see her there; didn’t want me to be traumatized by that experience or make the long journey from Los Angeles to Chowchilla.

When I got there I looked around at all the people and all the banners equating prison with torture and talking about the way prison destroys families, and takes mothers away from their children. It hit me right then how much bigger this was than me. I expected to go to the rally and have my isolated experience until I realized we were all there for the same reason — that everyone there had lost people in their lives to prison to a degree that was the same or worse — usually worse — than what I experienced. Hearing the cry of hundreds of people, the cry of anguish, and also this cry of strength and resistance all at the same time . . . hearing that collective voice left this seed in me and it’s been growing ever since.

ASR: Was there anything in particular about the day that struck you?

KT: I was so moved listening to everyone talk about their mothers or sisters or nieces in prison. One young woman spoke about how her relationship with her mother was really hurt by incarceration and they never quite recovered and that is so true for me too.

Another moment that had a huge impact on me was when people read quotes from people inside. In one quote a woman described needing medical attention and a doctor inside told her “she was old and was going to die soon anyway.” And you know, when you’re in prison you’re stuck with those options; if that is what your doctor is going to tell you, what recourse do you have? I started to realize that a lot of dystopian literature was not really fiction. It was very startling for me to realize that our country is in a situation as bad as the kind of dictatorship you see in V for Vendetta or that 1984 is not too far off the mark and neither is Brave New World. This is not fiction, this is not some far-off awful future, this is right now.

ASR: It is right now and also embedded in the foundations and history of our country. I’m so glad you showed up for that rally and allowed yourself to have that experience. How did your experience at the Chowchilla Freedom Rally affect your relationship to your mom and how has it shifted your art practice?

KT: It left a huge mark on my art practice and my relationship with my mother. I started collaborating with my mom. I would call her and ask her about details of her time in prison. It was very sensitive; talking about her experience in prison and me sharing my experience of having her locked up was hard for both of us. Mostly it created a lot of openness between us and allowed us to pick apart the guilt that she felt about being in prison and the anger I experienced when she was gone.

Through speaking to my mom and being at the rally, I realized her incarceration was not something that she did to my family or me. I realized that this is something that the state did to both of us. This trauma and inability for her to take care of herself and us was not a product of her simply being irresponsible. Finding words for that was really important. After she got out she would always apologize for abandoning me. Any time I was mad at her, it would always come back to that and she always thought that I was upset because of her time in prison. That was really, really hard for a long time because I had no words to tell her to stop apologizing. Now she and I have an open dialogue about prisons. She is very supportive when I go to rallies, she’s been really supportive about me speaking out, and she is supportive of my art process.

My art process has changed, too. As I become more aware of systemic oppression, I think a lot about my responsibility as an artist to make work that highlights these issues. This can be really hard because sometimes thinking too much about a work kills the inspiration!

Installation view of Kati Teague’s series Have You Seen My Mother?, three paintings and replica of a prison cell

ASR: The body of work you made about your experience of your mother’s incarceration, Have You Seen My Mother?, was chosen for the Irwin Awards at UC Santa Cruz — I think it’s great that the art department recognized the power and importance of your work. Can you describe the pieces that were in this show?

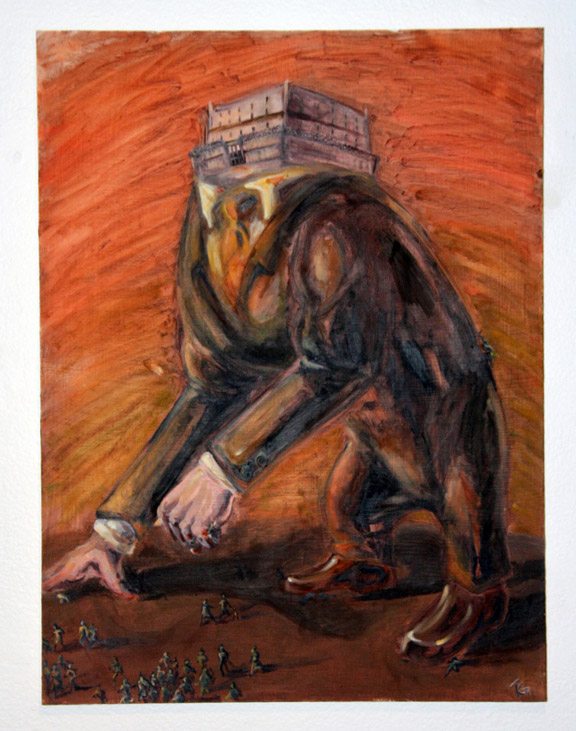

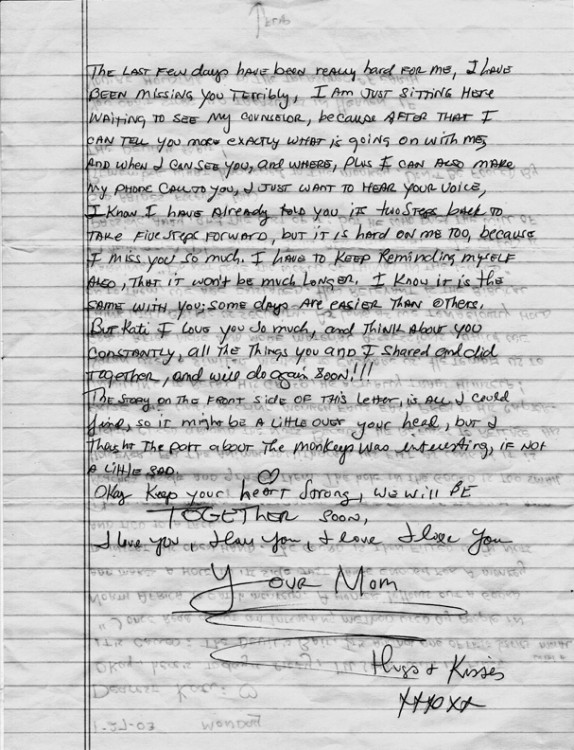

KT: Have You Seen My Mother? consisted of three paintings, a replica of a prison cell, and large-scale reproductions of letters exchanged between my mother and I while she was in prison. The paintings ranged from grotesque metaphors of the prison industrial complex to very literal, personal representations. In the piece I’m In the Prison Business I painted a business-suited monstrosity of a prison with a head that was gobbling people up and smashing them. This is how the prison system actually works and feels in our lives. This was my mother’s favorite piece!

Have You Seen My Mother? is also the title of the second painting of a little girl pointing a gun in the face of a cop crouched down before her. In the background there is the Central California Women’s Facility (Chowchilla). I painted it thinking furiously about how helpless I was as a child in the face of my mother’s imprisonment. Is it that unreasonable to think about saving our loved ones from the torture of confinement, with violent force if necessary? I don’t think so.

I then created a replica of a prison cell that people could interact with. It turns out that is something that artists and activists have done in lots of different ways. I wanted people to get an understanding of what I was talking about in a very physical way, to put their bodies in that space even just for a moment.

ASR: I’m interested in the biggest painting of the person on the phone behind the glass; I know this one is very personal to you.

KT: Yes, one of my strongest memories of this period of time is talking to my mother behind glass while she was in jail. The moment I sat down to talk to her on the other side of the glass, reality just fragmented. It was so surreal. It didn’t feel right or normal. As a white, middle-upper-class person who had no previous experience with incarceration, my only exposure to this environment was through T.V. shows — until it happened to me. So, I painted myself behind the glass. I didn’t want to paint my mother behind the glass because I didn’t want to put her back in that context, back in jail.

ASR: What was it like to paint that painting? The other two — the prison monster and the one where you are confronting the cop — are more imaginative but the one of you behind the glass is rooted in an actual memory. What was it like to return to that memory through that painting?

KT: It was exhausting. I talked to my mom about what color that part of the jail was and I looked at photographs of myself at that age. The more I painted, the angrier I got. It was also empowering to paint those lines myself and take that experience and make it mine and not something that was forced on me.

ASR: Has this process been healing?

KT: Immensely. I’ve experienced enormous healing for myself. Now this struggle feels less about me and more about the current state of prisons. It definitely changes the angle from which I come to prison abolition.

ASR: Can you say more about that?

KT: During the show, people shared with me what they learned about prisons and that was great. One young woman came up to me and told me that she met her father for the first time while he was in prison and that her brother is locked up right now. For someone to feel comfortable telling me that, I must have really made myself vulnerable — that let me know I was on the right track. Through this process, I gave some power back to myself and my mom, and hopefully that young woman, too. I wasn’t coming to the work with the anger of my childhood anymore, I was coming at it from the anger at the injustice of this being done to millions of people and families right now.

ASR: Absolutely. I am thinking of the case of Marissa Alexander, the mother in Florida who was sentenced to twenty years for firing warning shots during a violent attack from her husband. Just like that, the system took her away from her child and her family. As a result of public outrage, she was recently granted a retrial but there are countless other women and people who are locked up — whether it be for self-defense, as a result of their drug use, for petty crimes and so on — and their incarceration leaves countless children without their parents. I’ve heard you talk about how your personal experience is an exception to the people who have the most exposure to incarceration. Can you say more about this?

KT: Most people who have parents in prison have it so much worse than I did: mothers taken away for six years to life, children put in the foster care system after a parent is locked up, children who’ve met their parents for the first time behind glass, people in solitary confinement who are not even allowed visits, mothers not allowed to touch their children, people not allowed to see their partners, parents in and out of jail.

As an upper-middle-class white kid, I was taught that people who do bad things go to jail. The logic was that if there are more people of color in prison, there are simply more criminals of color and there is something more violent or deviant in anyone who is not white or middle class. And even when my mother was in prison, I had a whole support network; my stepmother and father took care of me, I was able to continue going to a private school, and my friends’ parents took care of me. Because my mother was white, and her crime was “white-collar,” the people around me were more likely to ask themselves if she deserved to be in prison, and if I deserved to have my mother taken away from me. I cannot at all imagine what this would have been like for the child of anyone who is already criminal in the eyes of society.

I honestly think that the reason Have You Seen My Mother? got such a good reception from the predominantly white students and parents viewing it is because the bodies depicted and spoken about were white and therefore, did not “deserve” imprisonment. I think it’s vital that the people with power are aware that they are more comfortable sympathizing with white suffering and white “criminals” than they are with indicting the systemically racist, misogynistic, and classist violence of the prison system as a whole.

ASR: This makes me think about the very popular Netflix series Orange Is the New Black that is based on the real-life experience of Piper Kerman, a white, upper-class woman who spends one year in federal prison — she is obviously not an accurate representation of who the prison system targets. The show uses the rhetoric of people making “bad choices” that land them in prison, rather than highlighting the systemic oppressions that you just mentioned. And the entire show is framed through the character’s whiteness, making it appealing to white audiences and in effect, using whiteness to substantiate the violence that communities of color have experienced forever.

KT: To be honest, I didn’t get past the second episode. I read the book, and in it Kerman does speak about misogyny, racism, and classism in prisons. There are resources provided in the back of the book for those who want to get involved in the struggle to end imprisonment, and for those who have loved ones inside. She used her privilege to get white people to listen, and since it is mostly white people who hold the keys to the cages, I think that’s important. Nevertheless, it is telling that this show is not based on one of the many books written by people of color who have been or are in prison. I’m torn, though. I can’t say the show shouldn’t exist at all because white people are more likely to listen to me now since they’ve seen that show. It’s tricky.

ASR: It is tricky and I hope people get involved and do more than consume the show as entertainment. Let’s talk about your organizing against jail expansion and in support of prisoner rights. Can you talk a bit about the organization Sin Barras and the work you all are doing in Santa Cruz?

KT: Sin Barras is a prison abolition group that raises awareness in the Santa Cruz community around various issues including the Pelican Bay Hunger Strike, the poor medical conditions in the county jail — over the past year there have been three deaths in the county jail and we are currently organizing against a proposed jail expansion in Santa Cruz.

The policing in Santa Cruz is very intense — under the Sit & Lie law, just putting your feet up on a park bench can get you arrested. But of course it’s not enforced on anyone except the poor and homeless. People get incarcerated and are in and out of the system due to homelessness. On April 6, we rallied at the county jail and had a noise demonstration so those inside could hear us. I spoke at the rally, as the child of a formerly incarcerated mother and about the horrible medical conditions inside.

Kati Teague speaking at the April 6 rally in Santa Cruz about her experience as the child of an incarcerated mother

ASR: It is awesome you were able to speak out and share your experience. We need to hear more stories like yours. How was that experience?

KT: I was definitely shaking. Because my experience was the “lite” version of how a prison can wound your family and ruin your life, I didn’t feel I had the expertise to talk about it; the idea that victims of the system are experts was also new to me. As I spoke, I realized that telling my story was not selfish, but very important. Story by story, we can begin to build a clearer picture of what prisons do to us, our families, and our communities, of the monstrosity we are fighting.

ASR: I’m wondering if you can describe what you remember about the time your mom was locked up? What was the impact on you?

KT: I remember vividly the day that I found out she was in jail. She was supposed to pick me up at summer camp and instead, my dad picked me up. Kids know when something is wrong. He told me she was in court and I assumed that meant jury duty. My dad started to cry and I had never seen my dad cry. Later, I came to understand that she was in jail.

My mother was the buffer between my emotionally abusive grandmother and myself, so not having her at home was very detrimental to me. I was lucky to have a roof over my head and food, and I could stay in school, but I did withdraw. I got really angry. I became vulnerable to a lot of abusive relationships because I was reaching out for support that I didn’t want from my family.

I remember getting her letters. I remember not wanting to be home when she called because it was too hard. I remember crying in class and her incarceration being a huge secret. I hated that. I wanted to talk about it all the time. After she got back our relationship was completely fractured. I didn’t feel like I knew her. It was hard to respect her authority and her way of dealing with that was to give me everything I wanted because she felt like she owed me that.

Having a loved one in prison is like having a relative die, but you know that they are still alive somewhere. Saying that prisons destroy families is not just some empty phrase; it’s the truth.