Proposal for a Museum: Questions on Expansion

After the last submission for our series Proposal for a Museum was published on Open Space in February, we invited Byron Peters, Matthew Post, and Xiaoyu Weng to join us in a conversation responding, collectively and critically, to the series as a whole. The following text, written by Peters and Post and including input from Weng, provides some of the key points addressed in that discussion. —grupa o.k.

grupa o.k. has asked us to provide a brief evaluation of its series Proposal for a Museum along with some thoughts on SFMOMA’s impending hiatus and expansion. The following questions and interpretations therefore revolve around a central concern that we might, following Lenin’s famous question, pose as “What is to be done?”

We notice (first) that very few of the submissions in the series function as proposals proper (which we could define as documents that articulate a distinct “plan”). Rather, they largely appear as hypothetical critiques of the present or, even when they outline a desired scenario, focus on overturning the current and historical conditions of the museum rather than on plotting out something altogether new.

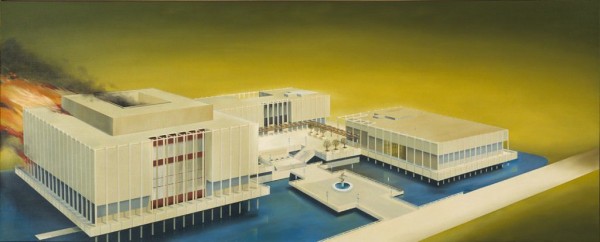

This “critical” reflex is to be expected; indeed, as Uruguayan artist Luis Camnitzer has argued, the critique of the museum is as old as the museum itself. Even within the utopian considerations of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s Museum of Unlimited Growth, or conversely, the catastrophic imaginings of Ed Ruscha’s painting The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, the museum’s inherent value is assumed by way of its reworking or even proposed destruction.

Take, for example, Dana DeGiulio’s Proposal for a Future Museum. While framed as a direct proposal, it instead lays out a disruptive roll call of past forms of institutional critique. This document could be seen as a sort of end point of critique, whereby critical attitudes within the history of the art institution present themselves explicitly and finally as the institution itself. This is to say that, like many of the other proposals, DeGiulio’s risks reaffirming (in the form of critique, absurdity, and hypothetical dreams) the concept of the museum as such.

On the other hand (and more in tune with our own position), perhaps her proposal suggests an unraveling from which the museum cannot recover, in which its auratic “here and now” [1] becomes dispersed beyond reconstitution. What her composite museum really demands is that institutional critique be channeled into something (some institution) that no longer resembles its current state, a “becoming something else” (to quote Ben Kinmont on those who “leave” the art world), or that engages more generally the project of “becoming different” [2] (to quote feminist economist Kathi Weeks on envisioning different notions of “work” and “non-work”).

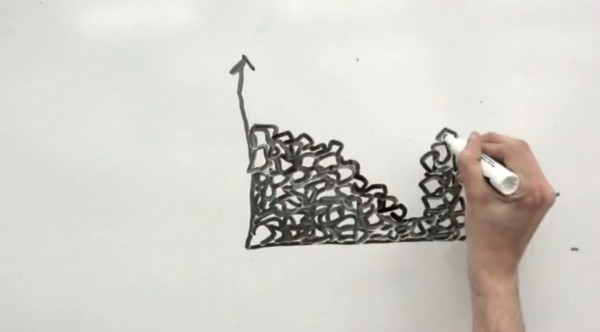

This (we would venture) might be a “something” without the monetizing, securitizing, mausoleum-like conditions discussed and countered in many of this series’ proposals. And while the museum’s hiatus and expansion at least opens up this possibility, we are hardly convinced that such “becoming” needs to take the form of architectural expansion. Indeed, insofar as expansion is a path legitimated by the growth models built into capitalism, we worry that it promises simply to affirm and renew with greater intensity logics already in motion in the modern museum: more spectacle, greater commodification of experience, a touristic mentality, and so on.

Although we are skeptical of some aspects of Daniel Marcus’s ambivalent reclamation of the “Babes At The Museum” phenomenon, his neologism “Selbstbildwert” (which he defines as museum visitors’ embrace of “social capital in the Instagram age”) points to a central, if otherwise unremarked, concern: As the audience incorporates, through social media, the museum and art into a low-level form of celebrity—as backdrop or mise-en-scène—museumgoers also produce and modify conceptions of the museum. In this coproduction of institutional identity, we might discover another impetus for expansion: as traditional forms of publicness disperse into various forms of mediation, architecture (and architectural spectacle) must expand. More and more space is needed to secure ever smaller and more fragmented bits of attention. In this sense, SFMOMA’s expansion compensates for, and attempts to house, the dispersal and reinvention of social life on new hypermediated terms.

Marcus dreams of harnessing and redirecting this coproduction for the ends of a more unruly sort of social and public life. We wonder by comparison if this equation—as mediation increases, architecture expands—is a devil’s bargain. Indeed, we might ask, simply, why expand at all?

SFMOMA states that the “expansion is about much more than the extension of the museum’s physical footprint; it’s about enhancing all the experiences we offer our visitors.” But this rather over-familiar language of extension and enhancement exists alongside the more prosaic task of housing a newly donated collection, namely that of Doris and Donald Fisher, cofounders of Gap Inc. This is not exactly Walter Benjamin unpacking his library (whereby “the historical object removed from pure facticity does not need any ‘appreciation’”) [3]; this is an expansion to house the art that wealthy people bought. Is this transfer from a private space (that of the Fishers’ collection) into quasi-public visibility really a benevolent “gift”? Or is it merely an opportunity for all to continue a rather recognizable model of “growth” whereby limited publics may view a previously enclosed collection within a system of rent (admission fees, etc.)?

In this light, it should be understood that SFMOMA is updating and decentralizing the processes of what Marx and others have described as “primitive accumulation.” Traditionally, the tendency of accumulation (in the logic of economies and museums alike) means the “outside” is systematically enclosed into an “inside.” But in tune with the contemporary philosophy of neoliberalism, this older economy is increasingly inflected by a semipermeable model of adventurism and expansion; the “gifts” of the former enclosure are bestowed upon new and diverse publics for the purposes of pre-scripted participation, “the experience economy,” legacy, or cultural capital.

SFMOMA Director Neal Benezra states that “the expansion is broadening access to our collection in ways that foster a sense of community ownership of the collective cultural riches of the city.” But for us this “sense of” ownership resembles too much the vantage point of the precarious tenant; it places the museum as a rentier of “collective cultural riches.”

A few of the proposals imagine the disconcerting results of such development. From the perspective of a future archaeologist, Monika Szewczyk pictures the excavated SFMOMA as “a curious conflation of art space and airport, full of amenities that, she concludes, appear primed for shuttling people past the art at record speeds.” Szewczyk’s archeologist reminds us, too, that accelerated obsolescence haunts capitalism’s passion for the new: “shortly after this renovation, the museum was subjected to accelerated ruination—this was the newest trend in art-making that started around mid-century 2050.” We are reminded of similar end points, such as William Morris’s portrayal of architectural monoliths becoming storage facilities for waste and societal byproducts,[4] or the case of DeGiulio’s Future Museum, where the institution is composed completely of its own site-specific disintegrations, ruined and renewed in one gesture.

We would, by contrast, pose the possibility that “expansion” might take a different form entirely. If, as Terry Smith offered in “You Can Be a Museum, or Contemporary . . .,” “the remodernist modern/contemporary museum continues to serve contemporary artists by steadfastly demonstrating the look of somewhere not to be,” perhaps the goal might simply be to redistribute the museum’s immense energies somewhere else. This could, in the very least, amount to an increased advocacy for spaces for art free of gift shops, of art-as-tourism, or composed of something other than dizzying storage facilities for privately owned value. In other words, with the museum as an expanding frame of reference, we might look to an imaginative demand as sort of counter rhythm, an equal and opposite force to “productive” expansion in general. As Marcus evinced, and as we also think, “to resist the encroachment of capital in the present climate, therefore, means harnessing the museum’s resources against the logic of productivity, elevating time-insensitive activities above the “proper” (i.e., productive) use of space.”

What is to be done? We hope that the above reflections ask for a sort of unraveling (a “something” which might be unrecognizable within many current identities and agendas of the museum). We will make two modest proposals, which might begin to undo the logic of privatization we describe above and to hold the museum to the promise of its public relations. First, the museum should abolish fees outright for admission and membership as, for example, the Dallas Museum of Art has already done; in the current language of the museum, this could be seen as extending SFMOMA’s Art for All proposal to the entire institution.

And second, the museum should make permanent its temporary program during closure of offsite projects and support for community partners—and indeed should extend its resources, expertise, and collection further to otherwise underserved and sorely underfunded arts institutions in the Bay Area. But there is no need to brand and pre-script this expanded field: this program could be reconsidered as a platform for a much-needed redistribution, an open response to the expanding privatization that grips San Francisco and urban centers in general. Enacting these proposals would begin to realize a “community ownership of cultural riches” that will otherwise remain a convenient rhetorical pose. This would be an expansion worth embracing.

—

1. Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. H. Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 221ff.

2. “The self at work could thus be judged in relation to a self that one might wish to become and both work and non-work time could be assessed in relation to the possibility of becoming different.” Kathi Weeks, “Life Within and Against Work: Affective Labor, Feminist Critique, and Post-Fordist Politics,” ephemera journal 7 (1), 2007, 248.

3. Walter Benjamin, “Edward Fuchs: Collector and Historian,” Illuminations, 235.

4. William Morris, News From Nowhere, ed. D. Leopold, Oxford University Press Inc., New York, 2003.