Tracing the Plot

Imran Qureshi, Blessings Upon the Land of My Love, 2011; site-specific installation at Bait Al Serkal; image: domusweb.it

The 10th Sharjah International Biennial — cocurated by Suzanne Cotter, curator at Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, and Rasha Salti, creative director at ArteEast, with associate curator Haig Aivazian — is titled The Plot for a Biennial. The exhibition draws on the idea of “a treatment for film, replete with a plot, characters and motives,” inviting artists, filmmakers, musicians, writers, and performers to respond to key words and themes, including “treason, necessity, insurrection, affiliation, corruption, devotion, disclosure, and translation.” The biennial is proposed as “a platform for multiple conversations with a distinctly worldly perspective, yet thoroughly engaged with the city of Sharjah, its past and present, and its political economy centered on trade and translation.”

Intrigued by the premise and excited about the possibility of a revealing narrative emerging from the endeavor, I set out through the streets of Sharjah to see the exhibitions that extend the biennial into the city. There is an acute sense of familiarity as well as an intangible distance always present for me in Sharjah. Conscious of the close vicinity of mosques and construction sites, I found that meandering through the Heritage area where some of the exhibitions are housed feels like an intrusion into the everyday life of the local community. The most successful projects for me are the ones that interact with the site in such an intimate way that they become one with the spaces they occupy, inviting to the local community as well as the biennial audiences.

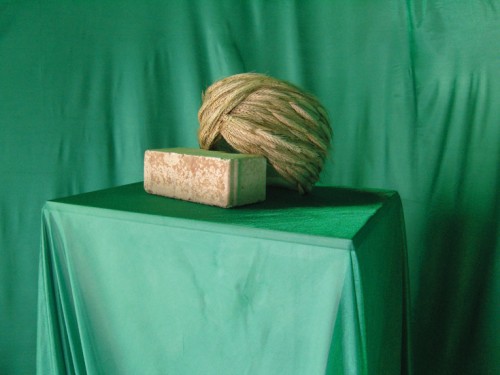

Imran Qureshi’s Blessings Upon the Land of My Love (2011) is a site-specific installation in the courtyard of Bait Al Serkal, a heritage building and a former hospital in an otherwise peaceful neighborhood in the Emirate of Sharjah. Using the same attention to detail Qureshi utilizes in his contemporary miniature paintings on view at the Sharjah Art Museum, he animates the courtyard with red drips and splotches, transforming it into a chilling reminder of past massacres and present bloodsheds. “Based on the theme, I was interested in the architecture’s space and my own vocabulary as an artist,” Qureshi states. “In this courtyard, I saw a quietness and sadness. The courtyard, that was central to the region’s architecture and historically a peaceful enclave in homes, has now been replaced with violence in the Middle East and Pakistan.” Qureshi was awarded the Sharjah Biennial Prize for “a site-specific work conversing with the culture, history, and political realities of the region.”

The collective Slavs and Tatars‘s project, Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz, is a refuge after a full day of battling heat and jet lag. The banner invites you in: “Long Live Long Live! Death to Death to!” According to the artists, the phrase “affirms the celebratory gesture and condemns the revenge and rhetorical justice which often undermine true popular revolutions and uprisings.” The implied opens the project to an array of other interpretations.

The installation feels at ease with its surroundings. Taking its inspiration from the city’s history of commerce, it is set up as a temporary tent, serving orange blossom–infused tea and dried mulberries. It offers shade in the form of Mehrabas filled with colorful stitched messages, slogans, and new aphorisms from the Polish resistance movement and the Iranian revolution: “Help the Militia: Beat Yourself Up!” or “Only Solidarity and Patience will secure our victory” translated into Farsi. I am specially intrigued by the interaction of the traditional with the political, the playful manipulations of language and patterns, and the invitation for dialogue through the seduction of the space and the rituals. The green space glowing with reflections of neon lights flickering in the mirror mosaics offered an alternative space for contemplation.

“Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz looks at the unlikely shared heritage between Poland and Iran and, in particular, the revolutionary potential of crafts and folklore behind the ideological impulses of two key modern moments, the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and Poland’s Solidarność in the 1980s, bookends to the two major geopolitical narratives of the recent past, the communist project of the 20th and Islamic modernism in the 21st centuries.” Friendship of Nations comes out of two years of analytical research conducted for publication 79.89.09.

I will continue to explore some of the projects at the Sharjah biennial in my Open Space posts. Meanwhile the controversies around the biennial continue and the conversations around the dismissal of Jack Pereskian and the censored projects at the Sharjah Biennial have become the focus of its coverage. There is an online petition by Rasha Salti and Haig Aivazian, two of the curators of the biennial, calling for the international art community’s support accompanied by an eloquent statement by Mustapha Benfodil, whose installation Maportaliche/It Has No Importance was removed from the biennial. Sheikha Hoor Al-Qasimi, the founder and president of the Sharjah Art Foundation, has issued a statement deeming the work inappropriate in a public context, and is quoted as saying she is “personally overseeing the reinstallation of the work” (ArtInfo‘s April 13th article “Censored Algerian Artist Mustapha Benfodil on His Part in the Sharjah Biennial Controversy”). Pereskian has distanced himself from the petition, stating that “I am not an advocate of boycotting any institutions to effect changes in the Middle East art scene. I have always believed in the benefits of respectful dialog and routine interactions to effect change.” Mustapha Benfodil reacts: “As the director of the Sharjah Art Foundation, he ought to defend the principle of freedom in art and condemn censorship in all its forms.”

Meanwhile Caveh Zahedi is battling to obtain the rights to his film facetiously also called Plot for a Biennial. Shot in Sharjah, it chronicles the making of the film and Zahedi’s failure to abide by an unspoken rule: not making fun of the Sheik Sultan bin Muhammad al-Qasimi, the ruler of Sharjah. According to a NY Times article on April 13, “A Film Angers an Emirate Festival,” Zahedi’s film was cut from the festival because of a particular scene considered blasphemous by the foundation, where a group of Indian children dance to Bollywood-style music, with some of the movements choreographed by Zahedi mimicking Islamic prayer rituals.