The art of the infographic

We are suckers for the infographic. What good typography is to prosaic prose, the Tuftean figure is to otherwise ambivalent data. At least it does something on the page. At least it entertains, at least it delights, for a moment, even if offering only a coy invitation to scrape deeper to find out whether you should rethink upcoming demographic booms or find mystical beauty in the numeric rhythm of a railway schedule.

What’s peculiar about the precise and beautiful chart is the logic it scores in spite—or because—of the unwieldiness, softness, or subjectivity, of the data it represents. It’s as if we’re so grateful for the visual clarity (the argument) that we’re willing to give a pass on methodological rigor.

Take, for instance, Andrew Kuo’s seductive charts recording a weeklong series of a Bright Eyes concerts in New York. What could be more subjective than “how good was that encore?” What could be less putatively subjective than seven multicolored extruded bar graphs, USA Today-style? You know it’s personal but it induces an experience of the impersonal.

Of course this is the point. We’re so awash in data that we cannot make decisions. We have access to enough GIS layers to drown a graduate program without ever giving us a useful conclusion. Just the act of making a simple infographic today is an acknowledgment of this predicament, an ironic avoidance of the databloat of our bullying zeitgeist. The “subjective” infographic is a guilty pleasure: we know it doesn’t represent reality any more than the Harper’s Index represents a statistical analysis. Because we can all enjoy it, it’s not quite masturbation; it’s more like really well-done porn.

The classic Statistical Analysis of the 1870 census is a good countermeasure if we get too jaded on the infographic (posted on Radical Cartography via Boing Boing). The graphics are simple and informative and handcrafted. These are worthy of wall-hanging, or maybe needle stitching into your aunt’s favorite throw pillow. Even if they didn’t represent something important about 1870 America (which they do), they’d be convincing studies in pattern, color and proportion. The earnest commitment to the data through graphic craft stands in for the authenticity of Kuo’s personal experience on show night.

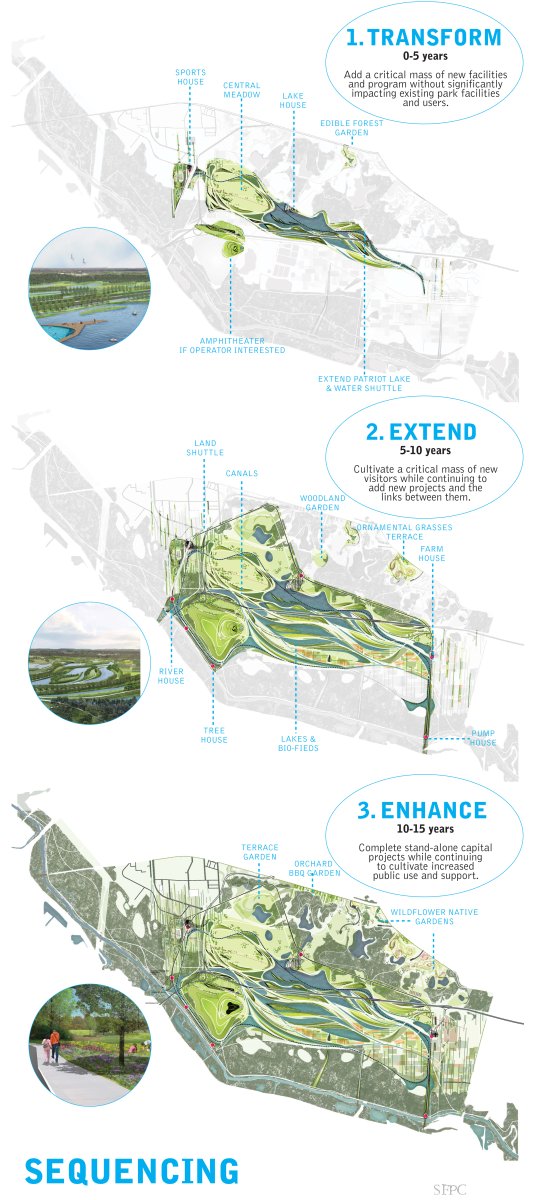

Earlier this month in a lecture at CCA, Charles Waldheim, the new chair of the Harvard GSD landscape architecture department, questioned whether the iconic graphics common in landscape urbanism proposals bear any authenticity to the data that supposedly drives them, or are just pretty seductions designed to win political support. These kind of graphics, used by starchitects to move public opinion to align behind large-scale projects, trade in the political currency of sustainability, and according to him, have become a visual cliche.

Which is a good reminder that the infographic is something between art and argument. We’re keeping it in mind as we venture into the realm of infographics ourselves. Wherever the data come from, they are a point of view, nicely wrapped.