My Own Private Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge

My mother-in-law recently came back from a visit to her brother’s apartment, where she discovered his old fridge photos all stuck together in a big wad, and proceeded to peel them off one by one. The difficulty was compounded, she explained, by hundreds of tiny fruit stickers that had been plastered all over the photos, absentmindedly. Was that what I meant by my old fruit label collection?

I’m still trying to figure it out, still tinkering with the idea of ephemera, mesmerized by the space between train tickets and skywriting on the scale of things that disappear. Why I was drawn to fruit labels in particular is a mystery to me. I had avoided the stamp bug, matchbox pox, postcard addiction (deltiology), and coin virus only to become a labelist, filling notebooks with minor variations on a theme. Since there is only so much diversity in the produce sections of big supermarkets, I spent most of my time hunting in mom-and-pop groceries and wholesalers. Sometimes the moms and pops thought I was stealing, but most of the time no one so much as blinked. I used a piece of wax paper, folded accordion-style, but most of the labels ended up on my wallet. Many featured Product Look-Up codes: the four- or five-digit numbers, preceded by a nine for organic produce or eight for genetically-modified, which tell cashiers what kind of apple or kiwi is in your basket. Some were all digits; others had no numbers or letters at all. I did, however, draw the line at barcodes.

Preserving ephemera used to seem subversive. After all, these were things that were born to fade into the background. But the idea that I somehow rescued them from oblivion was always an illusion. If anything, I merely delayed oblivion a bit, detaining the inevitable politely, as if by its sleeve.

I wasn’t really looking for patterns, but in order to make my growing collection portable and easier to rearrange, I affixed the labels to Post-it notes. Soon I developed a repertoire: one notebook was reserved for specimens I found in great abundance, another for the rare and unique. The more I collected, the better I got at discerning subtle differences, holding the entire collection in my head while sizing up a new label.

One particular source of pleasure was finding a label with a logo from a previous iteration, like this series of Turbana banana labels.

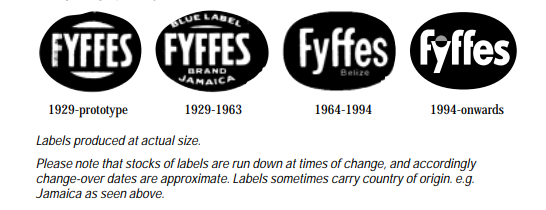

Turbana, it turned out, is a subsidiary of Fyffes, the oldest fruit brand in the world, and a pioneer in labeling and advertising. I’ve long admired the bold simplicity of the Fyffes logotype and the original Blue Label, which debuted in 1929, just as the market was crashing, to distinguish its bananas from those of a new competitor.

We can follow its evolution in The Banana Bulletin, a weekly company publication that seemed to take itself as a real journal. Older branding projects had stuck to the wooden boxes in which bananas were delivered to stores from their local ripening facilities, but soon it became necessary to distinguish varieties of produce and countries of origin by labeling the bananas themselves. Fyffes became synonymous with the so-called Blue Label, the mark of quality.

It also required more labor and was more time-intensive than anyone had ever expected. In 1929, for example, there was not yet a machine to affix labels. The work was done by two fifteen-year-olds using “a well-damped piece of an ordinary felt hat […] for retaining and imparting the right amount of moisture to the labels.” This seemingly tiny adjustment was a major change for overworked produce packers. They were now responsible not only for counting, strawing, and packing the boxes, but also for moistening and sticking labels with shoddy adhesive onto hands of bananas — at least three labels per hand—without falling behind on any of the tasks. (An informal performance test found that it took a teenager about one-and-a-half minutes to affix one hundred labels.) Eventually, a felt and copper tray that allegedly made this step more efficient was marketed to fruit packers for a mere few shillings. Ads featuring the new labels began popping up far beyond England: on a tram in Bucharest, an airplane in Norway, on a wall in Rotterdam next to a massive ad for a new film starring Emil Jannings.

Impossible to ignore, the Blue Label became a part of the cultural landscape. And in the years that followed, rival companies introduced their own brands and labels. I have most of them in my collection: Dole (formerly the Standard Fruit Company), Chiquita (the remains of the notorious United Fruit Company), and Del Monte.

Of course, it’s impossible to talk about bananas without talking about banana republics, a term originally invented to describe the situation in Guatemala, where the UFC worked hand-in-hand with the US government and intelligence agencies in a partnership that culminated in the UFC-produced, Eisenhower administration-approved propaganda film Why the Kremlin Hates Bananas. (UFC reefer ships — refrigerated cargo vessels — were also periodically pressed into service by the US Navy.)

The fruit that Fyffes and others were importing was grown on plantations in the West Indies and in Central and South America, where fruit companies like the UFC brutally remade the physical and political landscape to suit their purposes, developing “hundreds of thousands of acres of otherwise unproductive tropical lands,” becoming fiefdoms unto themselves, and even issuing tokens to the workers to use in their company stores. This stark colonial reality is often relegated to subtext in early text-based advertisements for Fyffes and other brands, while in others it is prominently displayed as an exoticized and racist celebration of naiveté. Take this 1930s Austrian toy, for example, which sold at auction not long ago.

Or this ad for the coffee-substitute Banan-Nutro at the online Banana Museum, which touts Stanley’s “Darkest Africa” for its tale of how “the natives prepared a gruel from Bananas and he found great comfort and regained his health.”

By 2004, my albums were brimming with hundreds of labels. I spent a year studying abroad in London — as everyone knows, one of the best cities on the planet for fruit labels — and found more variety there than I was used to back in New York. I’d travel north to Edgware Road from my room in Southwark and pick through mangoes from Cambodia and melons from Morocco. I preferred the smaller fruit stalls to supermarket chains like Tesco. The chains were mostly a wasteland of barcodes, while smaller vendors sourced fruit with what looked like art stuck to it. The fun was in never knowing what you might find. After a while, I wouldn’t have flinched to see my own face staring back at me from an unripe tomato.

I filled a new notebook with varieties from Europe and beyond: tinseled mangoes from Pakistan, Italian citrus, Iberian citrus, bananas from Cameroon, papayas featuring mobile phone numbers with unfamiliar country codes and bewildering sequences of digits. But around the time I was getting into them, produce labels were already disappearing or becoming homogenized, losing the rich, non-essential information that gave them character in the first place. Now you can just buy or trade for whatever you want on the internet.

There are as many ways of organizing a collection as there are collectors. More, in fact. So how does one go about organizing this finite richness? The late German game designer, author, and labelhead Eugen Oker effectively unorganized his collection, placing his labels at random on cardboard. Others seem to bear out the Yiddish term zamler, or collector, whose enthusiasm may be as meticulous as it is indiscriminate. The three-by-three treatment serves as a grid imposed on the unruly contents of these notebooks. I’m fond of the formality of this approach, which helps to focus the eye on a meaningful number of serial elements without overwhelming it.

Finite as it is, my own private Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge is never exhausted. I can find new resonances by reorganizing the labels around an arbitrary theme. If I flip to “C” for example, I find those from California: Oro Blanco grapefruit from Woodlake, pummelo from the Ward Ranch in Lindsay, cantaloupe from Holtville. There’s organic butternut squash (Tres Pinos), miniature seedless watermelon (Ladera Ranch), Sharlyn melon (Blythe), and honeydew (Mendota and Brawley and the 42nd Street brand in Yuba City). Navel oranges and cara cara, but also pomegranates, kiwi, cherimoya, and feijoa. You’ll probably never need to know the PLU code for feijoa, but just in case it’s 4265.

Grouped together in this highly unrepresentative sample, the labels form a novel agricultural map of a state called California without superimposing themselves onto a pre-existing geography. As Gerd Holzheimer has written of Oker and his collection: “suddenly the fruit stickers no longer appear only as stickers, as ‘important evidence for the history of trade,’ but as ‘millimeter-sized miniatures of contemporary history,’ as ‘time capsules’ in the sense of Andy Warhol, ‘semantic skeleton keys,’ in short: Wunderkammern.” 1

While these curiosities still exist in the wild, they may soon dwell exclusively inside the cabinet, replaced with precision laser incisions and blueberry ink for traceability. Then again, they’ve been prophesying the death of fruit labels for years now. As The New York Times wrote in its premature obituary almost fifteen years ago:

To producers, the stickers are messy, expensive and inefficient. “The industry knows that the days of the P.L.U. sticker are numbered and that there will have to be new systems,” said Don Harris, vice president for produce at Wild Oats, a national chain of markets, and chairman of the Produce Electronic Identification Board, an industry group. “Customers do not like them, and they don’t hold enough information anyway.”

Somewhere between my first and second notebook, a Georgia company named Durand-Wayland bought the patent for a machine that tattoos the PLU code directly onto the rind.

“With the right scanning technology the produce could even be bar-coded with lots of information: where it comes from, who grew it, who picked it, even how many calories it has per serving,” said Fred Durand III, president of Durand-Wayland. “You could have a green pepper that was completely covered with coding. Or you could sell advertising space.”

The future will be more efficient, less cluttered, and less fascinating, too — whenever it finally arrives.