Preliminary Notes on Forty Years of Writing Practice

1. The people come first. The writing is contingent on actual people; these people are my actual situation.

2. I fold, inscribe, compartmentalize. Minimize negative interference between the people and the writing, and try to maximize positive energy transfers between writing (or creativity) and people.

3. At the same time, continuous ideological struggle — internal, external, inside, outside. When we were younger, of course I didn’t recognize it as such, so there was lots of fighting, arguments, drama. Endless fussing and fighting to get out of the ideological limitations of lack of good ideas. Everything seems complex — and actually is. No wonder our parents had such messed up lives, messed up relationships. They had no clue, so of course, neither did we. We didn’t know how to cook, drive, change the oil, use a chainsaw. We were teaching ourselves. Autodidacticism. Our moms, dealing with endless mess and chaos, just trying to survive day to day. Raising seven kids on no money in East LA. Our dads, with their wild ideas, fucking everything up. Never any money, not supporting their families, etc. My brother didn’t start kindergarten on time because he had no shoes. My sister had rickets! Who even knows what rickets is nowadays? The upside was that both parents encouraged reading and writing, art and study. I internalized self-study, criticism, and self-criticism early, I was engaged in ideological struggle with myself early, because, one — it became clear that adults were damaged or deranged (to put it politely) and none more so than those who did not question authority and left their own ideologies unquestioned and merely “followed orders” — and two, you can accelerate your own learning and understanding by removing errors in your own thinking.

4. So many supposedly “psychological” problems are ideological.

5. One danger of ideological contradictions appears to be suicide. Be generous with yourself and your people around contradictions. (I am a mixed person.)

6. An active practice of reading, writing, study, is a process of ideological struggle and transformation. Which creativity demands. Creativity demands ideological transformation.

7. Women. Clearly the men who fathered us had failed to learn and understand something that women could have taught them. It wasn’t like the women hadn’t tried to communicate and weren’t patient. It didn’t matter, either, that males might be continuously engaged in fields and pursuits beyond their understanding or immediate experience of the females, whether it was in the arts or in trades that involved fierce competition or heavy labor. Often the males didn’t LISTEN; they’d been trained to get the hell out there and DO SOMETHING. When everything was wrecked later, when families were ruined or broken, the men ended up solitary, and it was then that they admitted in their self-pity that they fucked things up. Then it was too late.

8. I was honored to be ask to present at a reading and workshop for Street Poets, Inc., an organization devoted to mentoring incarcerated or formerly incarcerated or pre-incarcerated youth, community building and peace-making in Los Angeles, and during the Q and A, Taylor asked:

— how do you survive, how do you make it through?

Always listen to the women.

My father broke my mother’s nose, her hand.

But he didn’t die alone. Two of my sisters were there,

holding his hand.

Driving down the street you make a sudden maneuver to dodge a stalled vehicle and the guy on your tail flips a switch when you cut him off,

speeds up and cuts in front of you, screaming and flipping you off,

jams on his brakes so his bumper comes up on your vehicle,

you’re swerving out of the lane to evade, speeding to pass

in the traffic on the avenue — dusk falling — you’re laughing

because he speeds up, both vehicles beginning to race;

a woman’s voice rises to a pitch: “No, no, no!”

And you’re reluctant, but already you’re slowing.

Listen.

9. Listening, too, is such a critical part of ideological struggle. How can listening even be taught? Some people “hate” poetry because poets are always talking in some inner voice and listening to the inner voices. Isn’t the white space on the page of poetry about listening? Part of criticism and self-criticism is listening to yourself. Meanwhile, there’s often continuous outside noise, incessant distractions. Circumstances might seem more impressive, more phenomenal than discrete feelings, intuitions, ideas. Phenomena we’re told matters. Rent may be due; bills, contingencies press. DO SOMETHING. The culture is about either making money or spending it; it’s not about listening to quiet voices. Who will suggest to you that your own voice needs to be raised up? Who will say, listen to yourself? Only you can pay attention to your own thoughts. At the end of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, the unnamed narrator says, “Who knows, but that on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” Useful information is always coming across the lower frequencies. I know from personal experience on moss-slick rocks in the Stehekin River in the North Cascades National Park forty miles from my vehicle — should I ignore the little voice that says, “Those rocks are really slippery,” and mentally shrug it off and proceed at speed across them, without caution, I may find myself spun 360 degrees with my left boot stuck fast between rocks, both bones in my ankle snapped like a pencil. Landing in the river fully clothed, in shockingly cold glacial run-off, like I say, forty miles from my truck.

So, quiet, wasted internal noise. Listen.

10. A couple months after breaking my ankle in the Stehekin River (rescued by my wife and driven 1200 miles back to Los Angeles for surgery to reconstruct the ankle with a steel plate and screws inserted into both sides), as part of the LA delegation to the Mexico City Book Fair I hiked through the airport on crutches, met Daniel Hernandez (author of Down and Delirious in Mexico City: the Aztec Metropolis — he asked, “You here for the book fair, too?”), together we took a taxi into el centro. The book fair took place in tents in the main zocalo and we were lodged in a grand hotel across the plaza from the Palacio Nacional. Hundreds of thousands of people poured through the side streets and the plaza daily, going through the book fair or attending to business, sometimes crowding around street performers juggling fire and machetes (“this is why there were only twenty people at our reading in the museum earlier”). Hundreds of people stared at me as I plodded through the streets, the only person out of hundreds of thousands on crutches. Bystanders stared at me like I was some kind of walking target. One evening returning from talking book projects with Rubén Martínez and Luis Rodriguez at Café de Tacuba or a bar where Harry Gamboa Jr. plied the crowd with mezcal, the oily rain poured down as I hiked the dark streets back to the hotel, armpit muscles terribly sore as always, the bright lights of the lobby shining as I entered and immediately one of the wet crutches slipped on the smooth tiles and sent me crashing headlong to the floor. People rushed over to help. But I told them I was all right.

I was listening. Whether anything came through or not.

11. Who paid for the helicopter that Joe the Ranger called in? Who paid for that chopper setting down in the grass and willows and ten or twenty minutes later, lifting up, whipping up dust and foliage with me laid out in back on my backpack and gear, west over the mountains, over the high passes (I looked down and saw backpackers hiking over Cascade Pass) and shining Eldorado Peak, Eldorado Glacier? Who paid for the paramedics arriving in the ambulance at the Marblemount helipad, who drove me one hour west to the ER in Mt. Vernon? They showed me the X-rays in the ER, looking like someone had taken a sledgehammer to my ankle. My wife and daughter hiked two days east out of the mountains, (enjoying pastries at the wonderful bakery in Stehekin) then a bus ride to Lake Chelan, ferry boat ride back to the dock where my truck was parked, another day driving across the state to get to my sister’s in Puget Sound. How much did the helicopter ride, the hour in an ambulance, the surgery by Vahan Cepkinian MD all cost at Verdugo Hills Hospital? (Dr. Cepkinian I send you abrazos! Your ankle hiked to the tops of mountains and the the bottom of the Grand Canyon four times, without a squeak, without twinge, without an ache!) The whole thing cost me $50 or $100. Why? Because I got a union job in 1985 and I have paid union dues for thirty years. My wife and I work union jobs. I’ve been on strike and seen what it does to people when they win. We’ve had health care, bought a house, put our kids through college, ($25,000 to $35,000 per kid per year it cost us) and our kids graduated college without any debt. Because we are union.

12. The MFA poetry class I teach is a nonunion gig. No job security, no benefits, lower pay. We all do this because we love poetry, but that’s your typical nonunion bullshit without a union. You have to have an organization.

13. The individualist ideology in the arts and the in the culture in general is horseshit. If that’s all you’ve ever heard your entire life, that’s probably not your fault. But it’s still horseshit. Without an organization, all you will ever have is valid grievances. Your grievances, damage complaints and issues will remain valid. Forever.

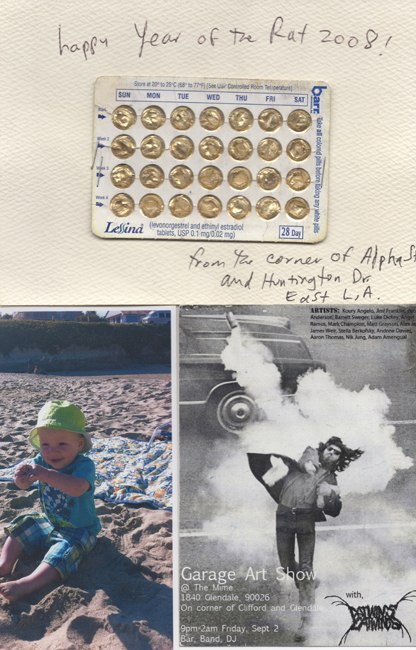

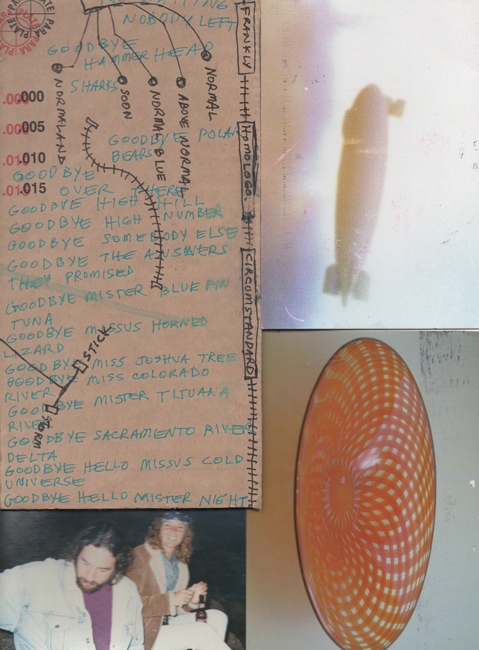

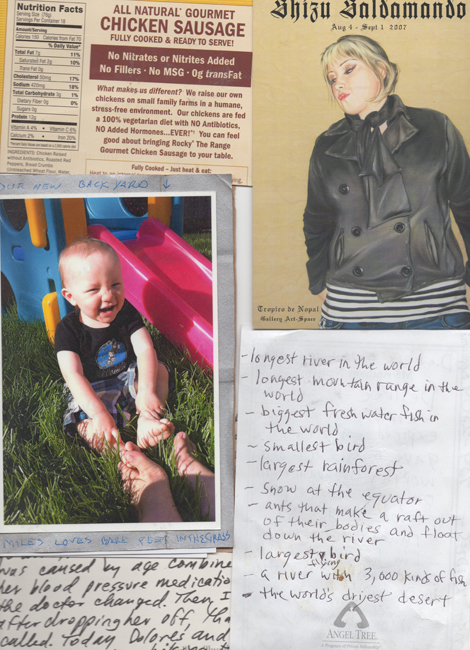

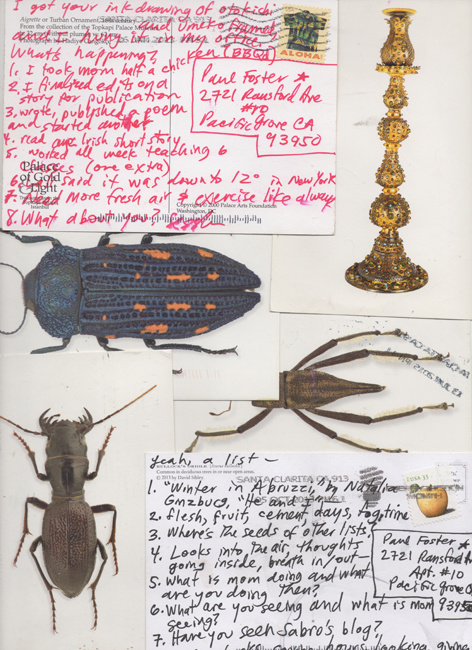

14. Always writing notes, letters, journals, ideas, annotations in margins of political economy, hundreds and thousands of postcards. When I was in high school, most of my ideas about language probably related to song lyrics, rock and roll, blues, pop, folk. Words, overheard, partially understood, perhaps not heard correctly, sometimes in another language.

15. When I was laid up for six weeks after ankle surgery, Joe the Ranger sent me a story he wrote about being Peace Corps volunteer in Peru and asked me for a critique. I annotated it and sent back the critique along with $100 and told him to have dinner on me.

16. Forty-five years ago when I was in high school, a friend found out that I filled notebooks with writings and drawings and then I them away. He asked for some. He took several downtown to Little Tokyo, to Gidra. Gidra newspaper was one of several radical community organizing projects where movement activists published articles and artwork against the war in Vietnam, against the displacement of older Asian immigrants from single room occupancy hotels in Little Tokyo (where the city was using Japanese capital to gentrify the area — before “gentrify” was a common verb), for redress and reparations for the Issei and Nisei interned in concentration camps in World War II, for solidarity with the Black Liberation Movement, support for the United Farm Workers’ grape boycott and farm workers unionizing campaigns, and other movement causes. My poems were first published in Gidra. I was proud that activists who were making things happen, making change happen, would consider my writing worthwhile to publish. If I wanted anyone to read my work and find it useful, it was the activists. If they thought my work worth reading, then it was. I didn’t care if it ever got published anywhere else or if I ever made money, but I was proud that these people liked it — the student activists and community organizers of Gidra, Amerasia bookstore in Little Tokyo and UCLA’s Amerasia journal, the activists of the Redress and Reparations Movement and the Japanese American Community and Cultural Center. (However, for the next twenty years I still threw most of my writing away. I had a cold eye for my own writing.)

17. When I was still in high school, I hitchhiked to Northern California to visit my younger brother, Paul, who was living in a foster home in Monterey, after running away from my grandmother’s house; he said he’d been beaten, robbed, assaulted, threatened, and shot at, in and around his alternative high school in Vallejo, where our father was from, and where our grandfather had once been head of security at Mare Island Shipyard. We hitchhiked south on Highway One (in those days there were hippies all over California and the rides were pretty steady) and my brother gave me his copy of Howl and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg. He told me to read it, handing me the classic little black and white City Lights edition. It blasted apart my stale concept of writing in general and poetry specifically; it renovated any idea I had about writing at that point.

18. The first poetry reading I went to (still in high school) was a reading by Charles Bukowski, who stood on a staircase landing in his chinos with his shirttails out, midway above the lobby of the Cal State LA student union building, which was packed with people, standing room only. Bukowski chuggalugged Michelobs out of a paper sack between poems and growled laconic, smarmy jabs at the audience. He was pretty good, I thought. I didn’t care about the show that the audience was entranced by, I thought the writing was good.

19. From readers like my brother, I learned that small presses were where you could find the best poetry. If it was new, if it was fresh, if you wanted something to transport you, let fresh air in the room, you weren’t going to find it in the magazine rack at the pharmacy or dusty stacks of back rooms in the public library. It wasn’t going to be stacked by the chewing gum and tabloids at the register. You had to locate some narrow bookstore, maybe like the Monterey Park Bookstore where the old Jewish guy with the huge gravelly voice — veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, they said — stocked Lowrider Magazines and Chicano lit (what there was of it at that time, La Raza newspaper, etc.), or the one off a Santa Barbara side street, kitty-corner from the Greyhound bus station and the YMCA (now a parking lot) where my dad used to get a room in the ’50s and ’60s — bookstores that my dad knew about and recommended (a successful alcoholic and failed Buddhist, proto-Beat poet himself), who had attended red wine poetry readings up and down the California, said he’d seen Ginsberg read in North Beach and attended lectures on Zen at the San Francisco Art Institute with Gary Snyder and Alan Watts (he named one of my brothers after Saburo Hasegawa). Just as the GI bill after World War II enabled a generation of working class guys like my dad to get an education in the arts, it enabled others in that generation to pursue interests in literature, accessing printing presses and mimeo machines and cranking out these folded and stapled countercultural missives and poem packets, sometimes lovingly letter-pressed, sometimes crude, always fresh. A live thing in the hand, with a human touch. Person to person — and not a commercialized corporate product. Readers like my dad knew where to find these bookstores.

20. I looked for small press books in every bookstore — chapbooks and books by Capra Press (Sicily Enough by Claire Rabe) and Black Sparrow Press (Art in the Court of the Blue Fag, by Wanda Coleman) out of Santa Barbara, City Lights Journal and City Lights books from San Francisco, Yardbird Magazine and IReed books from Oakland, Chicano presses like Lorna Dee Cervantes’ Mango Press in San Jose, Lalo Press and Chusma House from Fresno, Ediciones Pocho-Che from the Mission District SF, as well as tremendous small presses sending books from the East Coast — Curbstone Press from Willimantic, CT, Thunder’s Mouth Press, Grove Press, and the essential revelatory list of New Directions books out of NYC.

21. In 1996, Kaya Press out of New York City published my third book (not counting the translation of Juan Felipe Herrera’s wonderful hybrid Akrilica, which I co-translated with my wife and Stephen Kessler in 1989). I felt the same way about Kaya publishing City Terrace Field Manual that I felt about my poems being published by Gidra. It was an honor. In 2018, Kaya Press published another book of mine, City of the Future. It’s an honor for my work to be considered useful by Sunyoung Lee, Neelanjana Banerjee, Duncan Williams, and the staff of this astute, focused Asian American activist press.

22. At my reading last week at the Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research, I was asked, why do you like postcards so much? I pointed out the proto-Surrealist juxtaposition that happens with image and text every time you write a postcard. The question was really about the different between poetry and prose. And maybe what I should have said was that poetry is like a postcard, like a letter, it comes direct from one person to you. Prose is more of a collective form; it extends through the consensus of narrative formatting conventions like paragraphing, dialogue, setting, scenery, narration.

23. In 1988, Lindsey Haley, Ruben Martinez, and I chatted while I drove to San Jose to meet Juan Felipe Herrera. He was the most innovative, ambitious, and wide-ranging Chicano poet we knew of (and after two decades of writing, with a half-dozen brilliant poetry volumes, he still didn’t have a full-time job, driving hundreds of miles every week from one campus or another around the Bay Area, teaching workshops and adjunct gigs here and there, including at Soledad State Prison). We drove up to tell him how much his work meant to us. He invited us to participate in a Flor y Canto reading at Casa Zapata on the Stanford campus (site of previous Flor y Canto readings with Oscar Zeta Acosta, José Antonio Burciaga, and so many others), and then a barbecue at his house afterward. He grilled carne, green onions, tomatoes, with Nino Rota’s Fellini film music tinny out of a cassette player, as Juan Felipe passed out charred scallions, roasted jalapeños, and expounded on Rota’s felicity. The next day, as Juan Felipe drove his ’50s low rider classic car to San Francisco, I cassette-recorded an hour-long interview that I published in The Americas Review.

24. In 1978, I sent Lawrence Ferlinghetti a letter saying that City Lights was critically important to me. He sent a postcard back, thanking me. In 1978 I went to a reading by Kenneth Rexroth, and though I stood in line to get him to sign his book of translations of Japanese women poets, I regret now that I didn’t thank him for long decades of cross-cultural translations and anarchist poetics. (Around that time, I saw Bob Kaufman shuffling along Pacific Avenue in Santa Cruz, but I didn’t want to bother him. Like Rexroth, he was gone a few years later.) In 1987, I shook hands with Ernesto Cardenal at the Nicaragua International Book Fair in Managua and said that his work was of major importance. In 1990 at the Miami Book Fair, I met Allen Ginsberg in the elevator and in the hall where the American Book Awards were to be given out, told him his work had changed poetry for all of us. (He asked us, “What’s your favorite line of your own poetry?”) Over the years I’ve been lucky enough to thank Gronk, Harry Gamboa, Willie Herron, and Marisela Norte of Asco for their work, both in print and in person, telling them that as someone who grew up in City Terrace (in high school I recognized portions of a Willie Herron mural stacked against the wall in a classroom) their work crucially illuminated for me the great potential of possibilities. I was in San Francisco a couple years ago and told Alejandro Murguía that I loved his little 1980 book, Farewell to the Coast, and thanked him for his work. In 1997, I read with Jayne Cortez at Modern Times Bookstore in the Mission District, San Francisco, and got a chance to show her the epigram in my book taken from her poetry and thank her. Last week, at a reading at the Southern California Library in LA, Sandra de la Loza asked me to suggest tips on how to continue and go on working as a writer or artist. If I could have thought faster (by then it as at the end of a fourteen-hour work day), I should’ve answered that it’s necessary to understand the good work that has been done by so many across the years and feel grateful for the creative labor of these people, and tell those who have committed their lives to doing this good work that we give thanks.

25. I give thanks.

Comments (4)

Gracias yeh

Thoughtful ‘Grown folks’ work!

to give thanks. thank you, Sesshu Foster.

I love this writing.