Ownership: Omni Commons vis-à-vis The Lab (Part 2)

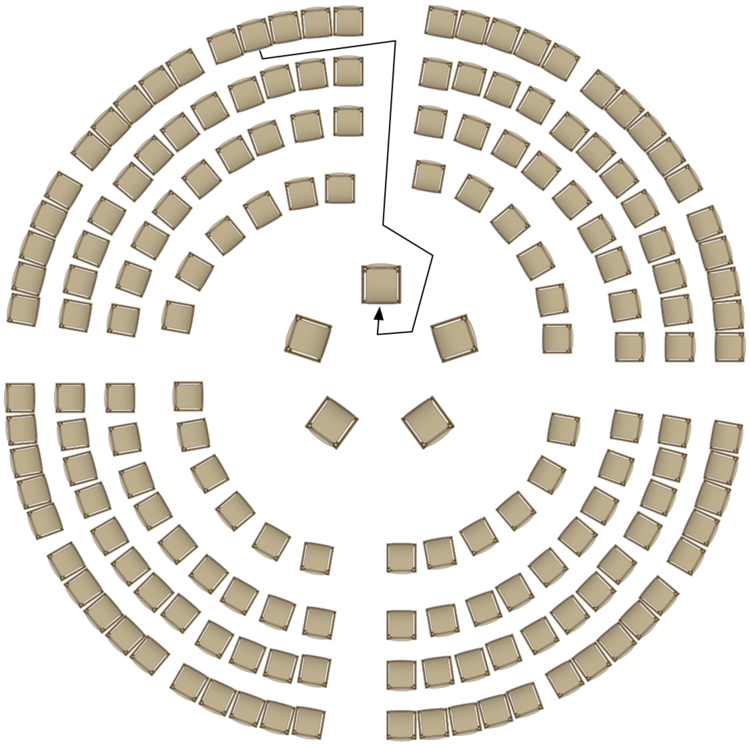

This is the second half of a fishbowl conversation featuring members of The Lab and the Omni Oakland Commons and moderated by Open Space [Read Part 1 here.], centered around issues of ownership, loosely described. In particular, both organizations were asked to respond to the prompt: “How do your organizations’ working practices engage or reflect an ideology around what it is to own, or hold in common?”

A second conversation, to be held on January 16 at the Omni Oakland Commons, will respond to concerns raised at this event. Please note that this is an edited transcript.

SUZANNE STEIN: I’m going to step out of the fishbowl now, and invite someone else to come in. Who will be the first brave conversant?

LAURA MILLER: I have a question for you. I’m Laura Miller. I’m a part of Birdhouse [arts collective at the Omni].

My question has to do with audience. I know the Omni has collectives within it, but there is [also a] shared idea of bringing in the community at large, or different communities. And obviously, The Lab has events and talks and artworks that bring in [different] audiences and communities. I guess my question would be about the structures of sustainability and value for you who are running these spaces and how they function in a more insular way. What are your experiences with and hopes and dreams for how that translates to the community at large, and then [for its] reciprocation?

From the November 15, 2015 Fishbowl Conversation at The Lab.

CERE DAVIS: What I was really excited about, and what I think Omni Commons was founded on — because it was founded on the Occupy movement — was a reclaiming of the commons and breaking down of the partitions. Who would we be to each other if we had the commons, if it wasn’t taken away?

ALEX SIZEMORE-SMALE: It’s hard to measure the success of a community space or evolving political project, but then, I see success at the Omni. It’s a community that can be very nebulous, but people are curious enough that you end up intersecting with people you wouldn’t otherwise, and learn about them in the process. And that’s special. It’s been really interesting to see myself and others grow as individuals and as a community through what has been an often uncomfortable and surprising process of reinvention.

DAVID KEENAN: We live in a language and a world that’s got a lot of words we might consider over-determined, in some ways: one person’s “community” might not be another person’s “community,” but they could both be talking about [the same] community at the same time with no apparent disagreement. And all the nuances around that only really emerge through a sustained imbrication and dialogue between people.

So what is “community”? You know, for some people, Omni’s community actually isn’t the community of people that go to the Omni: the community, the real community, is the community outside Omni, that we need to be — or are supposed to be — bringing in. And why is that? Like gosh, we have the space, why aren’t they just flowing in and making art and doing awesome stuff? I think because of the evolving nature of our understanding of community in Omni, we’re moving towards something that isn’t as singular: to say that actually, it’s a space for multiple communities. It’s a space for overlap. You know, like a multi-part Venn diagram overlap of communities. And in that respect, it’s sort of a liminal space. It’s a space for transection that isn’t always comfortable. Which is good because in some ways, we can construe the Omni as essentially — and I don’t mean this in a religious way — a kind of evangelical project, in the sense that we want that: we want diversity. We want people who aren’t used to hanging out in a [particular] community to come [in] and see how social difference can be positively negotiated. And for that reason, maybe Omni will always be a little bit uncomfortable.

MILLER: It’s a complicated question. You know, the words, the lexicon behind all of the endeavors in this room, their meanings are shifting. But more importantly, [so are] the values of the words we use. So for example, the word community — it’s a surface non-term. But there is an idea of being, for example, a space that has radical values that needs [community] to be liminal. But how do you realize that you’re in a place, an urban place with all these different groups, and want to share those values with people that may not know they exist, may never have considered it, may have considered it but don’t know their neighbor considers it? When we have these spaces, The Lab and the Omni, what can we hope to provide, based on our internal values? If you’re going to put on programming in The Lab, for example, or have people walk in the door to a culture at Omni which is completely outside of and trying to be outside of what we already know and are comfortable with, how do you convince people to walk in the door, and then sustain energy?

BEARD: I mean, aesthetics plays a lot into it. It is the art of seduction. The art of seduction and frustration. That’s desire. That is pretty much everything that we go for in for in life. We’re like, oh, that’s sexy, that’s wonderful, I’m infatuated with it. Then you get to know it and you’re like, fuck. [laughter] I grew up in a right-wing Christian environment, right? Where you go to church once, if not twice, a week, and you’re part of the community. And this community of people all believe the same bloody thing. They all believe it in slightly different ways. In some, kind of creepy ways; in some, kind of okay ways. But it’s not terribly reflective of the core value system, how the core system of value is created and how the system itself is created. That’s basically not for us to understand. You know, they believe that [this understanding] is in a higher sphere, literally. But the idea of the church always kind of intrigued me, because it’s made up of individuals who are complicit in maintaining that system. You have collectives, you have churches, you have institutions; they’re all just made of a bunch of people who believe in something, but each exists within a different sphere of reflectivity. I like artists who know people that I don’t know and who can bring those people into The Lab. And those people offer and say things about the work, or are reflective upon the work in a way that I would never have been or my friends would not have been, and who provide something that’s completely and utterly different and takes the rug out from under my feet.

SIZEMORE-SMALE: Something your question brought up for me is also the [problem] of trying to build a community or build an audience or involve more people in something that’s very much based on an ideal that is hard to understand. We say that we want diversity, we want to pull people in, we want to involve people with different backgrounds and experiences. At the same time, a lot of our ideals and values are so intellectually grounded that they are inaccessible to people without those resources or that education.

It’s even in the language. When you join one of our meetings, there are certain buzzwords that we use. It seems to me that sometimes our values, or the culture we’ve created, gets in our own way by making our community less accessible — something I’ve been thinking about a lot.

MILLER: I think someone in the audience needs to take my chair. Thank you.

JEANNE GERRITY: I’ll apologize in advance; this [question] is a little bit ignorant of the mission of the Omni and how you function. But I come from a background of working at art spaces and museums, and after a while, I became disillusioned by the fact that there is this kind of ownership of an art space by [its] funders. And ultimately, you have to do things according to what the funders want. I mean, it’s not always that direct, but there’s always that, sort of in the background. I’m just curious to know how you do simple things like pay the rents or buy the 3-D printers, or how you function within what is a capitalist system without having those values.

From the November 15, 2015 Fishbowl Conversation at The Lab.

SADIE HARMON: It’s hard. It’s a constant struggle. There are different aspects of the culture at the Omni that make it difficult. One of them is this decentralization of power, so you don’t have one person or a group of people who are figuring out how to raise money, for instance. You don’t have somebody like Dena, who says “this is the plan and this is how we’re going to do it.” At a really basic level, the way that we make money is the collectives pay rent or exchange other [things]. One of the basic tenets of the Omni is “for each according to their ability and to each according to their need.” Basically, it’s whatever people can contribute to use the space, they do. And that depends. That’s one way.

Then we also have individuals [and individual organizations] like The Lab, who donate different amounts of money. We’ve had Kickstarters and an Indiegogo campaign. But in a larger sense, we do most things through working groups. Right now we have a fundraising working group and a buy-the-building working group — it’s a group of people who come together in smaller meetings and try to strategize ways to make money.

Again, [we’re] trying to create a new system where we’re not beholden to large funders; we’re trying to create a system where we’re not beholden to a large grant, where we’ll have to fulfill certain expectations and we’re not beholden to one person.

GERRITY: What if one collective isn’t pulling their weight? Who would do something about it, or how would that work?

KEENAN: This is a really fundamental axis of tension and difficulty for the collective problem-solving abilities of the Omni. I think in some ways, it’s hard for anyone in the world to live in a capitalist system and figure out money [within] any organization. But for an organization that is explicitly anti-capitalist, it’s especially difficult because you end up with a group of people that actually don’t want to talk about money, aren’t very good at talking about money — myself included — and actually kind of want to avoid it. And that’s bad. The rent of the Omni is at least $15,000 a month, by way of a triple-net lease. By and large, it’s paid through donations, primarily from the member groups. So it’s like if you’re a member of a group, you kick down what you can, and then that helps to pay the rent for that group, and in this way all the groups together, then, pay for the Omni’s rent. But we’ve been actually running at a loss pretty much the entire time, in terms of our rent roll alone, although that is not our only source of charitable income.

How does that happen? Last year, we paid about $200,000 in rent. That’s a lot. None of these groups have endowments — it really comes, truly, from the community. Sometimes it comes from foundations, with discretionary year-end funding — if anyone’s here from one … [laughter] … I know a really good cause, if you just have like $10,000 lying around, wondering what to do. But we’ve gotten that, and that has been just the kindness of others, you know? The whole project was predicated on this quixotic idea, “build it and they will come,” in a way. We knew we didn’t have enough money to sustain the project even six months down the line, after we moved in. We’re constantly on the brink. You know, we could’ve (and should’ve) spent this year applying for the NEA Our Town grant or something [like it] and getting $250,000. But no one had time, because it’s been such a struggle just to keep the lights on and keep things going day-to-day, and to move past a state of initial becoming into something that’s established and more productive. Even with all the people involved in the Omni, I don’t think we were able to do that yet. We were able to get some money from Alternative Exposure grants again this year, [and from] some groups.

It always boils down to a skeleton crew of really selfless, committed people who ensure Omni persists and ends get met via a combination of taking on far too much work on the one hand, and by reaching out within our community for help on the other. And like I said, it’s an experiment. I wouldn’t hold it out like a recipe for success for any group. But you know, the fact that it’s persisted for a year is something that we can be proud of.

HARMON: That’s the thing about the possibility of the Omni and working within these systems, especially financial systems, and through other bureaucratic [ordinances] like building regulations and city codes and things like that, and the fact that people are willing to negotiate those in ways that aren’t horrible. On top of that, we want to be really critical of them and to be really critical of the way that we work within them, and of how we can operate in such a way that we’re consistently challenging them and we’re consistently trying to upset them. I find that really interesting and exciting. That’s kind of what the Omni presents an opportunity to do, that it’s not so much like financial solvency. As long as we can keep operating, we want to keep challenging [people] and being really critical.

IGNACIO VALERO: I think it’s not a coincidence that now we talk about commons, because basically, there is no commons. Or we no longer recognize the ones we have in front of us.

We are, in some ways — depending on who you ask, either [in] the eye of the hurricane or in heaven, in the Bay Area. [laughter] What are your relations to or reflections on the shared economy, the so-called shared economy? Because today, I feel that capitalism has basically co-opted and appropriated something that is very much in people’s minds and hearts. It’s a desire. It’s that seduction at which Madison Avenue is so fantastically good. And so my question is: how do you negotiate that, and how do you see that as a kind of noise in the system that is profoundly disturbing, in the sense that even they want to appropriate the concept, you know? It’s like what Rosa Luxemburg used to say. At the end of the day, capitalism will even appropriate socialism itself, you know? I’d like to hear your opinions and reflections and points [regarding that].

From the November 15, 2015 Fishbowl Conversation at The Lab.

MAN: It depends on what you meant by that phrase “shared economy.” There’s this concept of shared economy that I’ve heard with regards to Airbnb and Uber. And that is an utter, utter farce. Right? If you don’t agree, talk to me later. Fight me later, if you want. That’s an utter farce, right?

VALERO: I completely agree with you. We could include Facebook, we could include the entire whole thing, you know? I have nothing personal with Mr. Zuckerberg, of course. But how can you possibly become worth $30 million dollars in eight years?

MAN: Yeah, they’re appropriating, just like you said.

VALERO: That, to me, infuriates me in so many ways, because a taxi dispatch company now calls itself a technology company. You create this thing about techno this, techno that; but it’s just techno style. They don’t discover here the cure of cancer or some fantastic new way of spinning the atom or doing quantum whatever, you know? It’s just simply algorithms and a whole bunch of people working 24/7.

And so my point is, how do you open up and say the emperor has no clothes?

BEARD: That’s precisely what you have to do. And it’s funny, we have a surveillance camera up there. [laughter]

The idea is that it [sends] an image of whatever’s happening in The Lab to the homepage of the website. Every thirty seconds, it updates. The idea is to say: we live in a surveillance state. We don’t live in a democracy, we live in a pseudo-democracy that’s masking the surveillance state that protects capitalism. And the accumulation, the collection of data and the collection of information about us, is precisely how, over the last thirty years, the wealth gap has exceedingly, intensely changed. But the American perception is that we live in a democracy; the wealth gaps aren’t nearly as wide as they actually are. We’re all operating under these illusions. We operate under the illusion that Facebook itself is a commons. You know, that’s an illusion. People say, “this is so great, we can talk to our friends in public.” And it’s like, yeah, for fuck’s sake, go outside, go to the park. But instead of saying, “oh, fuck the surveillance state, we won’t reconcile with it.,” I say, no, let’s replicate it on this small scale and let’s figure out how to deal with it. The emperor has no clothes; let’s make that situation visible and ask, how, in the experimental laboratory of The Lab, would you change that situation?

DAVIS: I mean, I think it’s really hard to even understand the system you’re in and the effects it has on you. For myself, again, I like seeing my own purchasing habits change as a result — and I thought this for a long time, when I was in Seattle, but it was super isolating for a whole bunch of reasons. I mean, just seeing my own motivations change as a result of access to other people through the commons — you know, it’s like Cheers. You go to a place where everybody knows your name, even if you fucking don’t like them or whatever. [laughter] It’s really worth something.

KEENAN: Yes, at Omni, it’s like we’re always trying to disassociate ourselves from even appearing to enact anything like a “sharing economy” as conventionally understood. “Sharing” in its original sense has no function in a marketplace, nor is it a ”kind” of economy — by which we all mean a capitalist economy. Rather, sharing is a fundamentally different paradigm that actually counters, and can replace, the domination of the economic frame as the preferred way of ordering and understanding social relationships and moral politics. The “radical” sharing that Omni practices is one in which any appendage of “economy” is removed, or really just sharing in its basic form. Partly for that reason, I think at Omni people probably feel way less inclined to say that they “own” anything, whether an idea, space, or project. It can even become ironic how, in the context of collectivity, everyone’s also always trying to de-center their own speech acts, and un-privilege their particular points of view — even coming into this circle, we were like, should we really sit in the middle? [laughter] Maybe we should be on the edge.

I think making the invisible visible is important. By actually demonstrating what a real “sharing economy” could be, namely “sharing” absent any “economy,” [Omni provides] the relief needed to contextualize the commons’ invisible co-option by capitalism everywhere else, a diluting process that’s diffuse and all around us, you know? The problem is, it’s not super straightforward. Somehow with Uber, we know what to do. But walking into the Omni, people feel like they have to ask permission to be a part of that commons. They don’t know if they have the agency to engage non-transactionally. That’s been one of the biggest challenges: simply getting people to participate in that feeling of sharing, and to truly, radically share. Radical sharing requires a sort of internal deprogramming and a freeing of oneself to say, “It’s okay; we can do this together. I’m not stepping on anyone else’s toes by just participating.” Silly example; but we have a lot of food donations — and, feeling like you can just grab a sandwich that has been donated, and not worry about like —

SIZEMORE-SMALE: Paying for it.

KEENAN: Maybe you think you have to pay for it or go mop the floor because you ate a sandwich — and that’s how [laughter] the shared commons works? It’s all of those fears.

Download a PDF of the entire conversation here.

MP3 of November 15, 2015 Discussion (Note: MP3 is divided into two parts, but these do not correspond to the division between the posts on Open Space):

Part 1:

Part 2: