Matisse’s Couture Closet and "La Conversation"

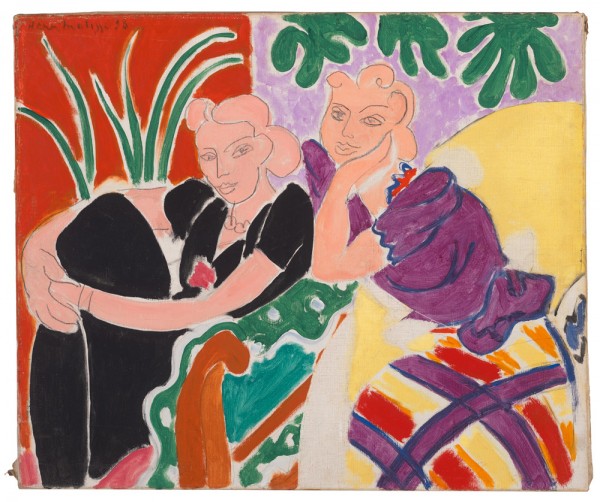

In 1938 Henri Matisse completed La Conversation (The Conversation), a vibrant exploration of color and design on canvas featuring two female models clad in couture. This painting, along with many other works in SFMOMA’s Matisse collection, was the focus of my research in preparation for Matisse from SFMOMA, which was on view at the Legion of Honor earlier this year.

In the process of that research, while skimming the publication Matisse: His Art and His Textiles, I came upon an illustration that brought my page-turning to a halt: a photograph of the same purple jacket and harlequin-patterned dress that are featured on the model to the right in La Conversation. Reading further, I learned that Matisse maintained a costume chest in his atelier, stocked with couture gowns for his models to pose in. This exciting discovery instantly prompted further research, and I would soon learn more about Matisse’s longstanding interest in couture, the apparent fondness he had for this particular dress in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and the fascinating history behind the model who wears it.

Matisse’s enthusiasm for fashion most likely grew from an early introduction to textiles during his childhood in northern France. The artist was born in 1869 in Le Cateau-Cambrésis (in a weaver’s cottage), and grew up ten miles south in Bohain-en-Vermandois, a manufacturing and textile town. By 1879, the town had forty-three textile mills producing various fabrics, including dress materials for fashion houses in Paris. In addition, Matisse came from a long line of textile workers: his mother, grandfather, and great-grandfather had all been weavers. At age 22, Matisse left northern France to attend art school in Paris, bringing with him an awareness of fabric and design. The artist claimed that while studying at the École des Beaux-Arts between 1895 and 1899 he “built up [his] own little museum of swatches.”

Although he was not yet collecting couture garments explicitly, by the 1910s Matisse would be surrounded by them. It was during this decade that the artist crossed paths with couturière Germaine Bongard, who rubbed elbows with many artists then living in Paris. During the war years Bongard hosted exhibitions in her boutique, showcasing works by Picasso, Léger, Modigliani, and Matisse, among others. This juxtaposition of modern art with the fashion of the day prompted the gazette Mercure de France to characterize Bongard’s boutique as a revitalized art salon, adding: “The painter Matisse is in ecstasy before the pleats in a skirt, he suggests the right kind of neckline essential to complete the architecture of a dress.” It is believed that Bongard produced couture clothing for Matisse’s wife, Amélie, each season. And when the artist’s daughter, Marguerite, came of age, she, too, received couture wear from Bongard, and purchased couture from other fashion houses as well.

The frocks and accessories collected by Madame Matisse and Marguerite would later join other costumes in Matisse’s atelier. However, the majority of these ensembles would not appear in his oeuvre until the 1930s, during an extremely creative period when Matisse incorporated fashion into his work and began collaborating with an important female model who would remain at his side for the rest of his life.

The focus of the artist’s La Conversation are two female figures stylized in contrasting ways, one in radiant color and the other in black, but if inspected closely, they are in fact strikingly similar. The two figures have more in common than the Matissean nose-to-eyebrow contour line: they were drawn from the same model, Matisse’s long-term assistant and muse, Lydia Delectorskaya.

Born in Siberian Russia in 1910, Delectorskaya became an orphan at the age of twelve, eventually emigrating from Russia to Harbin, China; after finishing high school she moved again, from Harbin to Paris. At age 22, Delectorskaya settled in Nice, France, where she found work as a film extra, a casino dancer, and an artist’s model. Six months after her arrival, Delectorskaya sought work with Matisse, who had been living in Nice with his family since 1917. He hired her as a studio assistant to aid in the preparation of the large-scale mural La Danse (The Dance). Although her appointment would last only six months, Delectorskaya made quite an impression on both Matisse and his wife, Amélie. The Matisses hired her back the next year to care for Amélie, who was in poor health at the time, and to maintain the household.

In her book With Apparent Ease . . . Henri Matisse: Paintings from 1935–1939, Delectorskaya describes how and when Matisse first noticed her as his next model: “[A]fter several months or perhaps a year, Matisse’s grim and penetrating stare began focusing on me … With the exception of his daughter, most of the models who had inspired him, were southern [Mediterranean] types. But I was a blonde, very blonde.” She continues, “Then, one day, he sat down with a sketchbook under his arm and, while I was scarcely paying attention to the conversation, suddenly spoke to me, ‘Don’t move!’ … And soon, Matisse asked me to pose for him.” Delectorskaya would take on an extremely important role in Matisse’s life, first as his model for the next six years, then as a studio assistant, and later as his caretaker until his death in 1954.

In the spring of 1938 while visiting Paris, Matisse and Delectorskaya attended the end-of-season sales in the city’s fashion district around rue de Boétie. Stocking up on costumes for his atelier, Matisse returned to Nice from Paris with an estimated six to ten couture pieces. One in particular was the diamond-patterned skirt and matching purple jacket seen in La Conversation.

Matisse incorporated the ensemble into numerous works, including not only La Conversation, but also at least four drawings and a rhythmic painting completed in 1938. Robe noire et robe violette (Black Dress and Purple Dress) bears some resemblance to La Conversation in that the two female models are posed in similar gowns, seated side by side. In contrast, however, the faces of the two models are left vacant, giving the work a rather raw, sketch-like quality.

Henri Matisse, Robe noire et robe violette (Black Dress and Purple Dress), 1938. Archives, H. Matisse; © 2014 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Henri Matisse, Deux jeunes filles, la robe jaune et la robe écossaise (Two Young Girls, The Yellow Dress and Plaid Dress), 1941. Archives, H. Matisse; © 2014 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

One other painting in particular, Deux jeunes filles, la robe jaune et la robe écossaise (Two Girls, The Yellow Dress and Plaid Dress), from 1941, features the highly recognizable plaid skirt on the model at the viewer’s right, although matched with a red jacket instead of a purple one. This switch leads one to assume that Matisse most likely was experimenting with pairing colors; here, red and yellow dominate the canvas. However, the story becomes more intriguing when we consider a photograph of Lydia Delectorskaya in the same plaid taffeta skirt, but wearing a matching plaid jacket. Perhaps, then, Matisse owned multiple variations of the same couture ensemble.

Lydia Delectorskaya, published in Henri Matisse : contre vents et marées : peinture et livres illustrés de 1939 à 1943

Henri Matisse, Study for Song, 1938. Archives, H. Matisse; © 2014 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Matisse was commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller in 1938 to complete a large-scale decorative mantelpiece for the Rockefeller apartment on Fifth Avenue. The mantelpiece, known as Le Chant (Song), pictures two pairs of women formed through curved contours and separated by planes of green and black. Although the final work does not overtly portray the plaid-skirted gown, the dress on the model at the top right seems vaguely related. In a study for the piece,the model on the viewer’s right is drawn in what seems to be a more distinct version of the dress, identifiable through the rounded or puffed fabric at the shoulders of the jacket and the striped skirt that hints at the original plaid. But more surprising to me is that the upper half of the sketch almost appears to be a working study for La Conversation, with the placement and position of the models, the outline of philodendrons in the background, and the wide-backed chair behind the seated model at right being the strongest similarities. Although the unique patterned skirt and jacket combination did not make its way into the finished commission, its inclusion in the preparatory drawing further validates that the ensemble was a critical addition to Matisse’s costume wardrobe.

Henri Matisse, Le chant (The Song), 1938; © 2014 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

One question that still remains unanswered is the origin of the couture pair. Based on further research with the aid of San Francisco public librarian Jean Sweeney, I found that a handful of scholars believe the plaid skirt and accompanying jacket may have been designed by Elsa Schiaparelli, the Italian avant-garde couturière who worked between the wars. It has been said that Matisse even called the plaid skirt his “Schiaparelli dress,” but this has not been confirmed. What can be confirmed is that the ball-button jacket and Parisian yellow, orange, and purple plaid skirt held a spell over the artist.

Jared Ledesma is curatorial assistant, painting and sculpture, at SFMOMA.

Reproduction, including downloading of Henri Matisse works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Comments (3)

Thank you for this glimpse through Matisse’s couture closet !

Would you know anyone who would like to purchase this from me! It is framed in a beautiful gold frame.

Tonya Snyder/Rodrigues

wonderful! I love Matisse’s work.