Lebbeus Woods, Architect: Jennifer Dunlop-Fletcher

Lebbeus Woods, Architect is on view at SFMOMA till June 2. Open Space is pleased to be hosting a series of posts on Woods’s work and legacy. Today, please welcome SFMOMA’s Assistant Curator of Architecture and design Jennifer Dunlop-Fletcher.

Lebbeus Woods and Conceptual Architecture, New York, 1970–85

In a 1971 essay, architect Peter Eisenman asked if conceptual architecture was possible. Eisenman was the founding director of the Institute of Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS), a small New York nonprofit organization that led the discussion on rethinking education, research, and theory in architecture and design from the late 1960s to the early 1980s through publications, critical debates, and exhibitions. Eisenman’s interest in conceptual architecture was focused on what he called a post-functional approach to form. He felt that it wasn’t architecture’s place to solve societal issues, and that the practice should focus on advancing formal concerns. But as Lebbeus Woods and others would demonstrate, Eisenman’s was not the only way of thinking about conceptual architecture.

One IAUS exhibition in 1976 included design proposals by Eisenman and architect Michael Graves alongside photographs by artist and “anarchitect” Gordon Matta-Clark. Matta-Clark’s Window Blow-Out (1976) featured a grid of vandalized windows in a housing project in the Bronx. The inclusion of this work dampened Eisenman’s conceptual torch with a dose of reality. Matta-Clark further emphasized the holes in the IAUS’s navel-gazing theory by sneaking in and shooting out the Institute’s windows.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Window Blow-Out, 1976; © 2013 Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In my estimate, Lebbeus Woods picked up the question thrown before architecture theory in the 1970s. Woods’s practice from 1980 until early 2012, when he completed his first built structure, was entirely conceptual. His architecture existed in drawings, models, texts, and installations. It was a practice in deep conversation with those of other architects, much like Eisenman’s had been, but it also recognized and powerfully addressed the existing built environment.

![Lebbeus Woods, Untitled [War and Architecture, High Houses], 1993; graphite and colored pencil on board. Courtesy Aleksandra Wagner.](http://sfmomaopenspace.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/lebbeuswoods_highhouses_WEB.jpg)

Lebbeus Woods, Untitled [War and Architecture, High Houses], 1993; graphite and colored pencil on board; Courtesy Aleksandra Wagner

Perhaps Woods’s biggest difficulty in sustaining a conceptual practice was to remain untethered to government or corporate funding. Woods, like many practitioners in New York in the early 1980s, was deeply suspicious of architecture’s financial backers and their imposition on built architecture. In a recent talk, architect Neil Denari spoke of Philip Johnson’s 1984 statement, “I am a whore and I am paid very well for high-rise buildings,” as a watershed moment. (In 1986 Johnson and John Burgee’s iconic 53rd at Third tower, known as the Lipstick Building, opened; it housed Citicorp and other finance firms, including Bernard Madoff Investment Securities.)

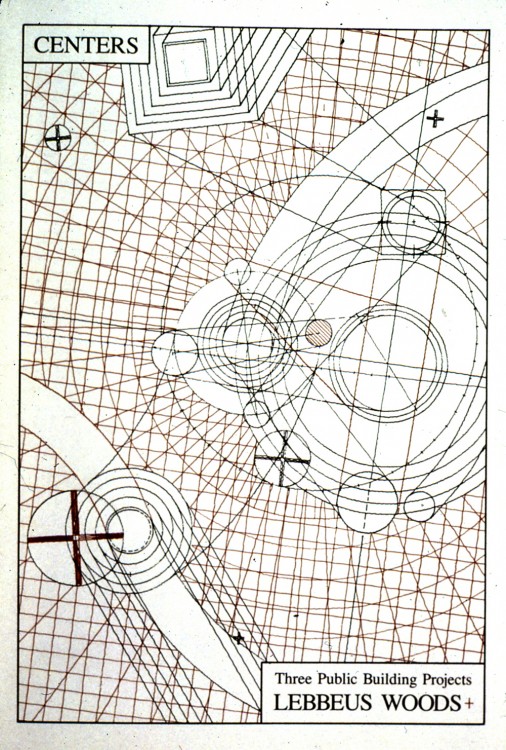

Lower Manhattan was common ground for a backlash against corporate culture; the neighborhood housed the Mudd Club and CBGB’s, where New York’s punk and performance scene thrived, and was the site of the graffiti art movement led by Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. It was in this setting that a small storefront gallery, appropriately titled Storefront for Art and Architecture, opened in 1983. The nonprofit, independent institution was founded by an artist and architect to foster discussion, experimentation, and reflection in art and design. Its first solo exhibition by an architect was Woods’s Centers: Three Public Building Projects, which opened in November 1984. It included three projects that challenged conventional urban grids and introduced the concept of centrality in designing public spaces. Woods’s work was included in eight Storefront exhibitions over the following 10 years.

While there had been similar conceptual movements in Europe, exhibitions like the ones at Storefront were part of a significant shift in the presentation and discussion of architecture in the United States. It was a moment of experimentation in unbuilt architecture and theory, and practitioners such as Woods, Diller + Scofidio, Neil Denari, Steven Holl, and Sanford Kwinter were actively exhibiting drawings or installations and writing about works that responded to a contemporary condition, instead of pursuing clients for built work. It was a badge of honor to operate outside the system of building codes and policies.

While many of the architects who presented conceptual projects at the Storefront for Art and Architecture in the 1980s and 1990s have since expanded their practice to include built work, Woods soldiered on in capitalism’s margins. Still, until his death in 2012, his work remained in dialogue with that of many of the architects I’ve mentioned, and he may have been awed at their courage at applying many of the ideas and theories that they had proposed on paper. After hearing Thom Mayne, Steven Holl, and Neil Denari speak about their relationships with Woods, I had the impression that no matter how far into building architecture each one ventured, they retained a deep appreciation for Woods’s ethical voice, which resonates in each of their projects.

Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher is acting department head/assistant curator of architecture and design at SFMOMA and co-curator, with Joseph Becker, of Lebbeus Woods, Architect.

Follow the Lebbeus Woods, Architect series here.