Wayne Koestenbaum: The Desire to Write

As we enter the last few weeks of our landmark exhibition The Steins Collect, Open Space is pleased to present a special two-part feature from essayist, cultural critic, and poet Wayne Koestenbaum. For this year’s Phyllis Wattis Distinguished Lecture, held on June 2, SFMOMA commissioned Wayne to write and perform a new work related to the exhibition. His topic: painting and writing. The result: “The Desire to Write.” Enjoy. (Part two, next Monday.)

Henri Matisse, Blue Nude: Memory of Biskra, 1907; The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland; © 2011 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Desire to Write about Blue Nude

Writing, alas, is never nude. Grammar clothes me with adjectives, prepositional phrases, and dependent clauses — a costume I didn’t choose, a costume that clashes with my native inclinations, which respect no division between the body’s secret holes and that bleak fringe of futurity where Matisse, in Blue Nude, 1907, might have wished to point, if paintings can point, if paintings can embody a wish to plunge forward.

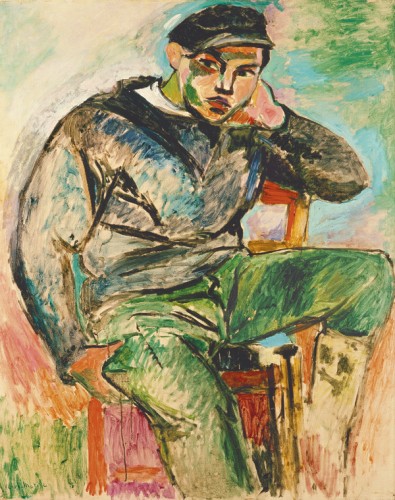

Henri Matisse, The Young Sailor I, 1906; Private collection; © 2011 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Desire to Write about Young Sailor

I could exorcise my love for this Matisse painting by writing about the patch of unadulterated blue, a triangle, which represents the receding plane of the sailor’s chair. Because this blue patch echoes the blue sky, mimicry modifies our ability to read the chair as a surface; instead, the seat becomes the brightest horizon we’ll ever receive an invitation to traverse and to destroy. I don’t want to write about the young sailor’s crotch; my desire to write about Matisse’s colors exceeds my waning wish to describe his evocation, in black and green, of (according to the catalogue) “a young fisherman he had met in Collioure.” Trying to pronounce “Collioure,” I pucker: an agreeable astringency.

Henri Matisse, Woman with a Hat, 1905; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, bequest of Elise S. Haas; © 2011 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Desire to Write about Woman with a Hat

Language’s impoverishment contradicts the voluptuous blue, green, orange, yellow, and purple that Matisse employs to render a woman whose hat is twice as big as her face. The green beside her head is a detail I seize to avoid being inundated by a bewildering superfluity of colors; I cling to this green as an island, a hermit’s cell, like the rock cleft where Willa Cather’s heroine Thea Kronborg, in The Song of the Lark, hides. I want to hide in Matisse’s combustible, multiform colors — especially the curvy hat’s preposterous blue. Am I espousing an aesthetics of the curve and of the swerve? Yes, but I’m also trying to be straightforward. I’d rather paint than write; now, with an unaccustomed sobriety of tone, I’m trying to contemplate why I might want to write about Woman with a Hat, and what I might say about Woman with a Hat were I to begin the unmanageable project of writing about it.

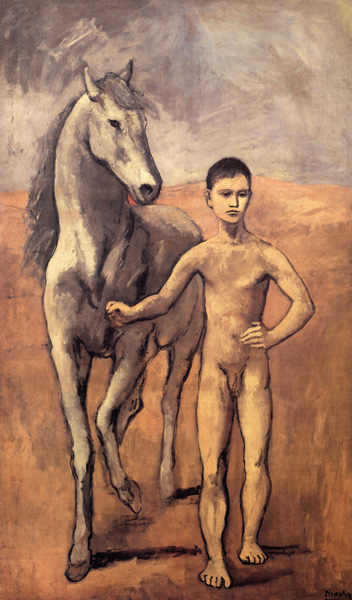

The Desire to Write about Boy Leading a Horse

The desire to write about Picasso’s Boy Leading a Horse is accompanied by — and nearly drowned by — a contrary desire: the desire not to write about Boy Leading a Horse. This entropic tendency, the desire not to write about Boy Leading a Horse, a desire I’m afraid to encourage, itself depends on a desire even more obscure — the desire to be the boy leading a horse, or to be that boy’s companion, his mirror image, his compatriot in the art of being nude. His feet grip the ground with a firmness equaling the firm black outlines surrounding boy and horse. These outlines, meaty and obtuse, give more satisfaction than any emotion we might attribute to the boy, a troubled cipher; the emphatic outlines, as if carved in wood, speak of the artist’s pleasure. I want the pleasure of the line-making hand more than I want the pleasure experienced by the boy leading a horse, or the pleasure of trying to approach that nude boy with these emphatic yet nebulous words.

Henri Matisse, Boy with Butterfly Net, 1907; Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund; © 2011 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Desire to Write about Boy with Butterfly Net

“I am an exhibitionist,” I said to myself, while walking home from the doctor’s office after my yearly physical — an appointment, this year, marked by an episode of unintended tumescence, mine, while my kindly general practitioner, a gay man my age, with hazel-colored wavy hair and hazel-colored eyes, palpated my testicles. In response to my arousal, he said, “You’ve been blessed,” and I’m still not certain, five hours later, exactly what he meant. Any painter is an exhibitionist; so is any model, even if underage. Children are the least remunerated exhibitionists in the history of Western painting; Matisse and his model, Allan Stein (subject of a novel by Matthew Stadler), shared, according to the exhibition catalogue, a “mutual affection,” though the only aspects of this mutuality that the painting captures are the mutuality of blue and green, the mutuality of red and brown, and the mutuality of realistic portraiture and its thrilling demise.

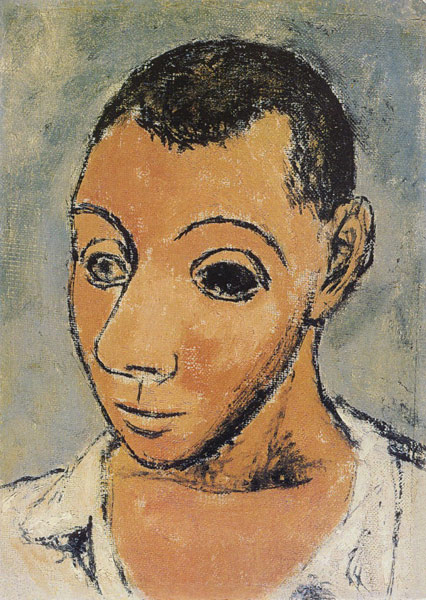

The Desire to Write about Self-Portrait

When I look at Picasso’s Self-Portrait, 1906 (or at a reproduction of it), my right index finger wiggles. My fingertip, in air or on my right thigh, traces the outline of Picasso’s face — especially the left eyebrow’s exaggerated semicircle and the oversized nose, whose comic magnitude makes Pablo seem a simpleton, a vaudevillian clown (Fatty Arbuckle, Buster Keaton, Jackie Gleason) we’d mock and reject. Alternately, the rotund nose, in conjunction with the Oedipally effaced eye, makes Pablo seem like sexy Gérard Depardieu in Bertolucci’s 1900. My right index finger, connected to an inner eye that wishes to prove the act of looking to be always covertly haptic, doesn’t know how to navigate the faint crosshatchings beneath the grey background. These crosshatchings might be the voice of the raw canvas itself, whose grain outsings the grey oil paint, either because Picasso applied only a thin layer, or because canvas’s élan vital, its honeycomb signature, overpowered his efforts to silence it. I want to write about this self-portrait because of its small size — a mere 10 1/2 x 7 3/4 inches. Its modest — infantile? — dimensions match the tidy boxiness of a paragraph, the container in which the desire to write compels me to dwell; I enjoy a paragraph’s outer edge, that moment when a sentence decides to terminate its journey.

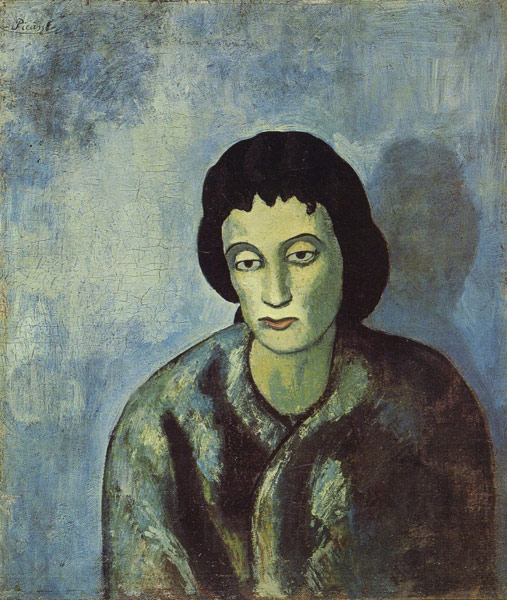

The Desire to Write about Woman with Bangs

The desire to write about Picasso’s Woman with Bangs may echo my desire to lift this depicted woman from her depression. (A painting can’t be depressed; this woman is only an effect of blue oil paint applied in 1902.) Because both the background and the woman are shades of complicated blue, the totality of blueness suffusing this scene allows no exit — no chance for a joke, a candy bar, a trip to the laundromat. My desire to write about the blue woman’s gloom (and thereby to reinforce it) is a diseased enterprise; I can’t alleviate an imagined woman’s desperation by writing complicated sentences, or by presuming that the color blue — when it swamps background and foreground, without distinguishing between woman and wall — is a logical dumping-ground for my hothouse empathy. This woman’s heavy-lidded eyes imply a roof of bone, a skull I’m eager, when I finish this paragraph, to ignore, so I can pay attention to the yellow-eyed beans boiling on my stove.

Henri Matisse, Landscape: Broom, 1906; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, bequest of Elise S. Haas; © 2011 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Desire to Write about Landscape: Broom

The looseness with which Matisse applied oil paint to his pencil sketch, in Landscape: Broom, 1906, a miniaturized venture into the louche and the smudged, inspires in me a wish to practice, in my own life, an analogous looseness — whether a looseness of morals (I will allow myself a variety of unsanctioned sexual escapades, and I’ll vow not to berate myself afterward) or a looseness of writerly technique, whereby I launch into the sentence’s open field without a plan, accompanied only by a wish to intensify my experience of random greens, violets, and pinks. My desire to write about this looseness — Matisse’s combination of chromatic opulence and austere omission — is a desire to participate in a practice of attentiveness that doesn’t shut down, out of prudence or shyness, when writing begins. Attentiveness intensifies as the sentence progresses; the writing session, whether fifteen minutes or two hours, affords a plein air openness to mental stimulation. I write to multiply occasions for stimulation and to magnify my power to experience pleasure. The pinkish-orange center of Matisse’s composition contains white horizontal brushstrokes, which seem to be moving left to right, as if striving to approach a blue semicircle that is itself yearning to approach a tree where small black and green strokes — animals, shrubs, or flowers — huddle. The purples and the oranges (especially the orange tree trunks) stimulate my body (I inhale more deeply, as if gasping); I don’t want to brag about my hypersusceptibility to purple and to orange, but I didn’t fly all the way to San Francisco from New York to lie to you about my clandestine relationship to color.

Henri Matisse, Interior with Aubergines, 1911; Musée Grenoble, gift of the artist, 1922; © 2011 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Desire to Write about Interior with Aubergines

Writing about Matisse’s Interior with Aubergines, 1911, seems the antithesis of the stupor incarnated by the five-petaled blue flowers that Matisse has plastered (with distemper) over floor and wall equally, in a room whose mood of reverie and escapism is Moroccan by proxy — the patterned, imageless universe of the Alhambra. Does the term “all-over” describe the abstract expressionist version of this Alhambran impulse, which, appropriated by Matisse, authorizes stasis and meandering as two sides of one ethereal coin? Matisse’s blue flowers, courtesy of Novalis, repeat. Their mandate to erase depth perception in favor of an entranced flatness allows me to become that giddy flatness by writing about it; writing about the proliferating, block-print-like flowers, I side with them. I ingest the flowers, and take on their no-nonsense wish to totalize, to level distinctions, to bliss out. I’ve lied; depth exists in this painting, but these mini-tableaux of depth are framed vistas that resemble flat panels. By writing about Interior with Aubergines, I want to legalize my own blue-flowered interior — my word-cave, the brainy hollow behind my eyes, where jasmine petals in my childhood house’s front yard are still unpicked and fragrant. Those flowers, in 1962, weren’t jasmine; of unknown genus, they embodied the numberless, the oppressively uncommunicative.

Henri Matisse, Red Madras Headdress, 1907; The Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania; © 2011 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Desire to Write about Red Madras Headdress

Last night, I dreamt that I was scheduled to give a piano recital, whose pièce de résistance would be Schubert’s final sonata. In the dream, I hadn’t mastered the sonata, and so, with relief, I canceled the recital, even though my brother had already inscribed it in his calendar, a notebook he considered sacred, not subject to the indignity of last-minute cancellations. In my fingers, as I informed my brother of the cancellation, I could feel the melancholy opening theme of the sonata’s first movement, a melody I realized I would never play in public; in my fingers, I could feel the injury I was inflicting on my family by canceling a concert that, though negligible, had become our only nourishment. Later in the dream, a large clump of orange-yellow wax fell out of my left ear; the wax was the color of the chair on which the woman, in Matisse’s Red Madras Headdress, 1907, sits — a yellow reminiscent of banana, papaya, summer squash, and Sauternes. In the dream, I bragged to everyone about my ear’s waxen trophy, this honeyed evidence of auditory prowess. Like Odysseus, I was now prepared to endure the song of the sirens; tied to the dream’s mast, I no longer needed a waxen encumbrance to shield me from a lethal melody.

[Do return for part two, next week]

Wayne Koestenbaum has published five books of poetry: Best-Selling Jewish Porn Films, Model Homes, The Milk of Inquiry, Rhapsodies of a Repeat Offender, and Ode to Anna Moffo and Other Poems. He has also published a novel, Moira Orfei in Aigues-Mortes, and seven books of nonfiction: Humiliation, Hotel Theory, Andy Warhol, Cleavage, Jackie Under My Skin, The Queen’s Throat (a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist), and Double Talk. His next two books, forthcoming in 2012, are The Anatomy of Harpo Marx (University of California Press) and Blue Stranger with Mosaic Background (Turtle Point Press). Koestenbaum is a distinguished professor of English at the CUNY Graduate Center, and also a visiting professor in the painting department of the Yale School of Art. He lives in New York City.