The Marriage of Figaro: With Anne Colvin (Part 1)

I don’t drink coffee, so let’s have a beer… My posts are always collaborations and are presented in two parts. Part 1 is a summary of a shared experience with my collaborator(s). Part 2 is a response often in the form of a project created specifically for this blog.

My first co-conspirator for this grand blog experiment is Scottish born Bay Area artist Anne Colvin. We agreed to have our project stimulated by a shared experience, and after reviewing our local options, we set off to SF Opera’s The Marriage of Figaro. Neither of us had been to the opera here, however we both have a relationship to opera in our past.

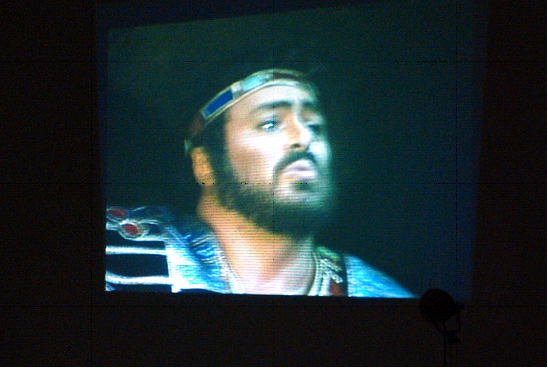

Anne Colvin is an artist, curator and publisher of the journal Skank Bloc Bologna. Her video and installation work is both poetic and in your face. Her work has been exhibited around the globe, most recently in Long Play: Bruce Conner and the Singles Collection as part of SFMOMA’s 75th Anniversary exhibition. She mines culture, most often in the forms of film and television for her source material, stripping back the narrative arc to mere moments, imbuing filmic strands with raw, sensuous, often jarring energy. To me, her work has a heightened awareness of time, frame, texture and gesture. Opera has featured in a couple of Anne’s curatorial projects; in So It Goes a screening of Pavarotti in a 1981 SF Opera production of Aida was juxtaposed with Julian Myers’s Riot Show, and most recently opera was included in the DJ mix for Skank Bloc Bologna Number Four at Berkeley Art Museum along with skank and Scritti Politti. Like her work, Anne is both graceful and frank. My type of gal!

My undergraduate degree is in theater and my first love is musical theater and opera. When I was ten years old I sang the title role in Amahl and the Night Visitors (Gian Carlo Menotti, 1911) with a small local opera company and I was hooked. True confessions – In high school and college I was the geek (or Gleek in today’s terminology) in choir and all the musicals. After college I attended a workshop where I studied stage direction with the innovative opera director Peter Sellars, and then began stage managing for a branch of the Minnesota Opera called The New Music-Theater Workshop where Philip Glass was developing a new work, as was NY playwright Mac Wellman. I stage managed for theater and opera until my late 20’s. Although life took me in a different direction, I will always be a fan of opera.

“Susanna” Danielle de Niese and “Figaro” Luca Pisaroni rehearsing in SF Opera’s The Marriage of Figaro. ( Dan Honda, Mercury News)

Le marriage de Figaro was originally a five-act play written by Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais in 1778 in France, just a decade before the storming of the Bastille. Louis XVI banned the play, but private readings proved popular, so in 1784 it was allowed to be staged publicly. The immediate success of the play led to Mozart’s operatic version in 1786. The central characters are the Count and his Countess, their servants, Figaro and his fiancée Susanna, and a host of comedic supporting characters. Set in Spain, Figaro is a comedic farce that pokes fun at the aristocracy with a storyline that revolves around the Count’s intention to take the virginity of Susanna before her wedding night. This was not simply the Count’s desire, but according to the concept of droit du Seigneur, it was the lord of the castle’s right to take the virginity of his servants. In a nutshell, wackiness ensues for the next 3 ½ hours and in the end the Count is outwitted, and Susanna remains pure for her new husband Figaro.

During the opera, Anne said that she kept framing the action on stage in very cinematic ways – she imagined a camera panning the scene and zooming in for close-ups. On the other hand, I was more interested in thinking about the very traditional experience of my fixed perspective in relationship to the frame (proscenium arch) and the action within. This single perspective forces you to work much harder to enter into the fantasy. I heard Michael Caine on NPR say that in film an actor needs to become/embody the character, but on stage you need to act. There’s an awareness on the part of the audience and the actors that the buy-in is more difficult to achieve because of the restrictions of live theater. Anne commented that initially she had a really hard time finding a way in, and that applying a vision of filmic spatial relations provided the access that allowed her to remain engaged. Films about painters and works of art, like Derek Jarman’s Carravagio (1986) and Eve Sussman’s 89 Seconds at Alcázar (2005) came to her mind. These films are both incredibly gorgeous, yet they’re specifically calculated to expose the cracks in the veneer, the backside of the story. The artist that was on my mind, Yinka Shonibare, is also engaged in the same sort of practice. Often utilizing the theatrical form of the tableau, Shonibare tackles issues centered on the creation of identity and its relationship to colonialism/postcolonialism and globalization. Shonibar’s work is stunningly lush, achingly humorous, and drives the viewer into that uncomfortable place of confronting what is fundamentally irreconcilable in history.

I hadn’t been to the opera or seen live theater since before my five year old son was born. To me, opera is synonymous with opulence and extravagance. I kept saying to Anne that this particular opera experience seemed humble. Humble, really? This was the word that kept coming back over and over. Film, no matter how real or gritty, keeps you at a distance. However, we were watching people on stage twenty feet away performing for us. Immediate, raw, human. On film, sound levels can be controlled, but during Figaro I kept thinking, “This is how loud someone can sing or play, and this is the quality of their voice or instrument as they negotiate the notes.” (There was a bit of amplification, but much less than any other opera house I’ve ever been in.) There’s risk involved in live theater, and the little flaws are what make each performance unique. What I’m stating isn’t earth shattering, but in a world where culture is primarily mediated for us through a screen of some kind, it’s a humble and important experience to watch people perform (theater, music, dance, spoken word…) live. As we watched the opera we were involved in the process of making culture happen, not simply consuming it.

Anne and I will create a project that responds to our thoughts on Figaro for next week’s entry.

Comments (1)

Sounds like an interesting project…